Abstract

Objective:

Psoriasis is an inflammatory skin disease affecting 2–4% of the world population. The objective of this study was to perform a systematic review and meta-analysis synthesizing the epidemiological associations between psoriasis and obesity.

Data sources:

We searched for observational studies from MEDLINE, EMBASE and Cochrane Central Register from 1 January 1980 to 1 January 2012. We applied the Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology guidelines in the conduct of this study.

Study selection:

We identified 16 observational studies with a total of 2.1 million study participants (201 831 psoriasis patients) fulfilling the inclusion criteria.

Results:

Using random-effects meta-analysis, the pooled odds ratio (OR) for obesity among patients with psoriasis was 1.66 (95% confidence interval (CI) 1.46–1.89) compared with those without psoriasis. From the studies that reported psoriasis severity, the pooled OR for obesity among patients with mild psoriasis was 1.46 (95% CI 1.17–1.82) and the pooled OR for patients with severe psoriasis was 2.23 (95% CI 1.63–3.05). One incidence study found that psoriasis patients have a hazard ratio of 1.18 (95% CI 1.14–1.23) for new-onset obesity.

Conclusions:

Overall, compared with the general population, psoriasis patients have higher prevalence and incidence of obesity. Patients with severe psoriasis have greater odds of obesity than those with mild psoriasis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Psoriasis is a common inflammatory skin disease that affects 2–4% of the world population.1 Patients with psoriasis present with erythematous, scaly patches and plaques that can affect any part of their body.2 The impact of psoriasis on patients’ quality of life is similar to that for patients living with insulin-dependent diabetes, depression and angina.3

Increasing epidemiological evidence suggests that patients with psoriasis may be more obese compared with the general population. Although the exact mechanism underlying the epidemiological association between psoriasis and obesity is uncertain, researchers have theorized that adipocyte elaboration of pro-inflammatory cytokines may exacerbate psoriasis.4, 5, 6, 7 Understanding the epidemiological relationship between psoriasis and obesity is also important for delineating risk factors for other comorbid diseases that may result from obesity. For example, obesity is a risk factor for cardiovascular diseases, type II diabetes mellitus, obstructive sleep apnea and osteoarthritis.8 Better understanding the strength of the relationship between psoriasis and obesity will therefore help ensure that future observational studies include adequate adjustment for the presence of comorbid obesity among patients with psoriasis.

In this systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies, we synthesized the current literature on the association between psoriasis and obesity based on epidemiological studies from around the world.9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24

Materials and methods

We searched MEDLINE, EMBASE and Cochrane Central Register using the following search criteria: ‘Psoriasis’ [Mesh] AND ((‘Obesity’[Mesh]) OR (‘Body Mass Index’[Mesh])). Our search was limited to English language, human subject studies published from 1 January 1980 to 1 January 2012. Furthermore, we manually searched the reference sections of retrieved articles for any additional studies that were not included in the initial search. To be eligible for inclusion in the systematic review, the original studies needed to fulfill the following criteria: case–control, cross-sectional, cohort or nested case–control design; evaluation of obesity in conjunction with psoriasis; and analyses that compared psoriasis patients with control groups. Specifically, the studies must have evaluated the prevalence or incidence of obesity as defined by physical examination, patient self-report, medical chart review or medical billing codes. Whenever body mass index (BMI) was available, we included studies that defined obesity as a BMI⩾30 kg m−2.

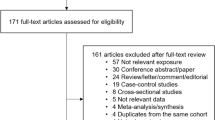

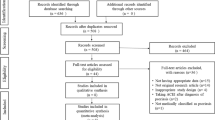

A total of 130 articles were retrieved from the initial search, and 8 additional studies were found from review of the reference sections (Figure 1). After manually reviewing all abstracts, 77 full-text articles were further examined. In all, 15 of these studies were excluded because they were reviews; 1 was a duplicate study; 5 assessed only psoriatic arthritis patients; 7 did not include a non-psoriasis control group; 8 were letters, commentaries or editorials without original data; and 25 did not report measures of association between psoriasis and obesity. After these exclusions, 16 publications were included in the meta-analysis. For the purposes of meta-analysis, one publication18 was treated as two studies, because two separate control populations were used in that publication.

Two reviewers (CTH and AWA) independently extracted the data and performed the systematic review, and any disagreements were adjudicated by consensus. The Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology guidelines were used to guide analysis.25 For each study included, we recorded the study year, country in which the study population lived, setting in which the study took place, study design, numbers of case and control subjects, age, gender, whether the results were adjusted for comorbidities, data collection processes (prospective or retrospective), whether the results were a primary or secondary analysis of the publication and whether psoriasis disease severity was assessed. To measure study quality, we used a previously validated six-point scale, with values of 0 or 1 assigned to study design, assessment of exposure, assessment of outcome, control for confounding, evidence of bias and assessment of psoriasis severity.26 Studies with a score of 0–3 were categorized as lower quality, whereas studies with scores of 4–6 were categorized as higher quality.26

The majority of studies were case–control in design and reported adjusted odds ratios (ORs). Studies that reported prevalence (n=15) were analyzed using meta-analysis, whereas the one study that reported incidence15 was summarized. To estimate the pooled OR, we initially used both fixed-effects and random-effects models of DerSimonian and Laird.27 For each study of prevalence, the crude ORs were identified based on the publication. In cases where multivariate adjustment was reported, the effect size and reported upper and lower bounds of the 95% confidence interval (CI) were log-transformed. The inverse variance method was then used to calculate the pooled OR. Study heterogeneity was assessed using the I2 statistic. Owing to significant study heterogeneity, reported pooled ORs are based on random-effects modeling.

Publication bias was assessed using visual inspection of a funnel plot of the study size vs s.e., with formal statistical testing using the Begg adjusted rank correlation test.28, 29 To explore sources of study heterogeneity, we performed meta-regression using prespecified variables and random-effects meta-analysis. Prespecified sources of heterogeneity included study country, subject location (ambulatory or inpatient), multivariate adjustment for confounders, prospective vs retrospective study design, ascertainment of prevalence vs incidence, primary vs secondary analysis, ascertainment of psoriasis disease severity, measure of outcome and study quality (0–3 vs 4–6). All analyses were performed using STATA Version 11.2 (STATA Corp., College Station, TX, USA). No funding sources supported this work. All authors have read and agree to the manuscript as written.

Results

We identified 16 observational studies with a total of 2.1 million study participants fulfilling our inclusion criteria. Among them, 201 831 patients had psoriasis (Table 1). Fifteen of these studies reported prevalence among patients with psoriasis, whereas only one study15 assessed the incidence of obesity among patients with preexisting psoriasis. Obesity was defined in most studies as a BMI⩾30, but a few studies used only medical diagnostic codes for obesity. Many of these studies assessed obesity as a secondary outcome in conjunction with prevalence of metabolic syndrome, but most studies adjusted for obesity independently.

All studies reported measures of association between psoriasis and obesity; the studies that found a statistically significant association after controlling for other covariates reported adjusted ORs ranging from 1.03 to 1.9 (Table 2). Meta-analysis revealed significant between-study heterogeneity (I2=98%). Using random-effects meta-analysis to account for between-study heterogeneity, the pooled OR for obesity among patients with psoriasis was 1.66 (95% CI 1.46–1.89, Figure 2).

Visual inspection of a funnel plot revealed possible publication bias, but formal testing with the Egger test did not reveal any definite publication bias (P=0.1). Meta-regression was also performed using prespecified variables to assess possible sources of study heterogeneity (Table 3). Studies that performed multivariate adjustment reported a significantly lower strength of association between psoriasis and prevalence of obesity (OR 1.41, 95% CI 1.26–1.58 for studies with adjusted OR vs OR 2.32, 95% CI 1.79–3.01 for studies with unadjusted OR, P=0.004 for comparison).

Four studies reported the relative association of mild psoriasis with obesity (Figure 3).9, 16, 18, 23 The pooled OR for obesity among patients with mild psoriasis was 1.46 (95% CI 1.17–1.82). Five studies reported the relative association of moderate-to-severe psoriasis with obesity (Figure 4), with a pooled OR of 2.23 (95% CI 1.63–3.05).9, 13, 16, 18, 23

Although obesity likely predates the diagnosis of psoriasis in most cases, one study examined obesity incidence over time among patients with psoriasis. This study was conducted using the General Practice Research Database, a UK-based cohort of patients treated in general medical practices. Among a cohort of 44 164 patients with psoriasis, 2760 patients (6.3%) had a new diagnosis of obesity during follow-up. When compared with a matched cohort without psoriasis, those with psoriasis had a hazard ratio of 1.18 (95% CI 1.14–1.23)15 for new-onset obesity.

Discussion

This systematic review and meta-analysis showed that the current literature supports an association between psoriasis and obesity. Specifically, compared with the general population, psoriasis patients are at significantly increased odds of obesity. Our meta-analysis of the cross-sectional and case–control studies showed that psoriasis patients have >50% increased odds of being obese compared with the general population. Where psoriasis severity data were available, the pooled OR for those with moderate-to-severe psoriasis was also significantly higher than that for patients with mild psoriasis.

Although the precise mechanism underlying the association between psoriasis and obesity is unknown, several lines of basic and translational research suggest that adipocytes and inflammatory-type macrophages may contribute to both disease processes. Adipose tissue is an active endocrine organ that has a key role in lipid and glucose metabolism, inflammation and coagulation, and insulin-mediated processes.30, 31 Macrophages are the key immune cell type that perpetuates inflammation within adipose tissue. Activated macrophages in adipose tissue stimulate adipocytes to secrete inflammatory mediators that establish and maintain an inflammatory state in obesity. Adipose tissue, especially visceral adipose tissue, then secretes bioactive products collectively known as adipocytokines or adipokines. The co-existence of psoriasis and obesity is at least in part attributed to the function of adipokines and their downstream effects.

The role of the various adipokines in psoriasis is an area of active investigation. For example, leptin is an adipokine that serves as an afferent signal of the nutritional and fat mass status to the hypothalamus and thereby regulates appetite and body weight.32 Hyperleptinemia has been associated with increased intima-media thickness of the common carotid artery and with arterial thrombosis.33, 34 Studies in psoriasis have shown that leptin levels are elevated in psoriasis patients6, 35, 36, 37 compared with healthy controls, and psoriasis is an independent risk factor for hyperleptinemia.35 Although an increase in pro-inflammatory adipokines is seen in psoriasis, a decrease in regulatory adipokines is also observed in psoriasis. For example, an inverse relationship exists between obesity and adiponectin, a cytokine that has an anti-inflammatory and regulatory role in atherosclerosis.38 In psoriasis, the adiponectin level was decreased in psoriasis patients compared with healthy controls.4 Furthermore, adiponectin level in psoriasis patients was inversely correlated with psoriasis severity and tumor necrosis factor-α levels.36

Although obesity likely predates or co-exists with psoriasis, one study examined new-onset obesity in patients with existing psoriasis.15 The authors found a slightly increased risk for developing obesity in psoriasis patients compared with controls. It is possible that some psoriasis patients are reluctant to engage in physical activities where their skin disease may be visible to others. Thus, in addition to genetic and immune-mediated mechanisms, behavioral factors may have an additional role in explaining the association between psoriasis and obesity. Although a few studies suggest that the use of tumor necrosis factor antagonists may be associated with weight gain in psoriasis patients,39, 40, 41, 42, 43 larger studies are necessary to elucidate the effect of systemic medications on obesity. This is one potential rationale for the stronger association between obesity and severe psoriasis. Alternative explanations might include a more active systemic inflammatory disease leading to greater alterations in adipocyte function, dysregulated metabolism and concomitant development of obesity and severe psoriasis.

This systematic review and meta-analysis must be interpreted in the context of the available primary studies. The methods for identifying psoriasis and obesity differed among the studies; while some studies used diagnostic codes to identify obesity, others used BMI measurements. Psoriasis severity was assessed in a minority of studies. The variations in the study findings were likely attributable to the differences in study design, patient population, and ascertainment of predictors and outcomes. Despite the potential heterogeneity among the studies, the directionality of the association between psoriasis and obesity is nearly uniform among the studies, and the overall finding from the meta-analysis is strongly supportive of the association between psoriasis and obesity.

In summary, this systematic review and meta-analysis revealed that psoriasis patients have >50% odds for obesity compared with those without psoriasis. Patients with more severe psoriasis are at higher odds of obesity compared with those with mild psoriasis. In patients with preexisting psoriasis, their likelihood of developing new-onset obesity is higher than those without psoriasis. Clinical recommendations to reduce weight in obese patients with psoriasis may have beneficial effects in both obesity-associated comorbidities and possibly their psoriasis severity. Future studies are necessary to elucidate the mechanisms underlying the association between obesity and psoriasis and to determine the impact of systemic medications used for psoriasis indications on modifying obesity.

References

Christophers E . Psoriasis—epidemiology and clinical spectrum. Clin Exp Dermatol 2001; 26: 314–320.

Johnson MA, Armstrong AW . Clinical and histologic diagnostic guidelines for psoriasis: a critical review. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol e-pub ahead of print 27 Jan 2012; DOI: 10.1007/s12016-012-8305-3.

Grozdev I, Kast D, Cao L, Carlson D, Pujari P, Schmotzer B et al. Physical and mental impact of psoriasis severity as measured by the compact Short Form-12 Health Survey (SF-12) quality of life tool. J Invest Dermatol 2012; 132: 1111–1116.

Shibata S, Saeki H, Tada Y, Karakawa M, Komine M, Tamaki K . Serum high molecular weight adiponectin levels are decreased in psoriasis patients. J Dermatol Sci 2009; 55: 62–63.

Coimbra S, Oliveira H, Reis F, Belo L, Rocha S, Quintanilha A et al. Circulating levels of adiponectin, oxidized LDL and C-reactive protein in Portuguese patients with psoriasis vulgaris, according to body mass index, severity and duration of the disease. J Dermatol Sci 2009; 55: 202–204.

Wang Y, Chen J, Zhao Y, Geng L, Song F, Chen HD . Psoriasis is associated with increased levels of serum leptin. Br J Dermatol 2008; 158: 1134–1135.

Corbetta S, Angioni R, Cattaneo A, Beck-Peccoz P, Spada A . Effects of retinoid therapy on insulin sensitivity, lipid profile and circulating adipocytokines. Eur J Endocrinol 2006; 154: 83–86.

Haslam DW, James WP . Obesity. Lancet 2005; 366: 1197–1209.

Al-Mutairi N, Al-Farag S, Al-Mutairi A, Al-Shiltawy M . Comorbidities associated with psoriasis: an experience from the Middle East. J Dermatol 2010; 37: 146–155.

Augustin M, Reich K, Glaeske G, Schaefer I, Radtke M . Co-morbidity and age-related prevalence of psoriasis: analysis of health insurance data in Germany. Acta Derm Venereol 2010; 90: 147–151.

Cohen AD, Gilutz H, Henkin Y, Zahger D, Shapiro J, Bonneh DY et al. Psoriasis and the metabolic syndrome. Acta Derm Venereol 2007; 87: 506–509.

Cohen AD, Sherf M, Vidavsky L, Vardy DA, Shapiro J, Meyerovitch J . Association between psoriasis and the metabolic syndrome. A cross-sectional study. Dermatology 2008; 216: 152–155.

Driessen RJ, Boezeman JB, Van De Kerkhof PC, De Jong EM . Cardiovascular risk factors in high-need psoriasis patients and its implications for biological therapies. J Dermatol Treat 2009; 20: 42–47.

Herron MD, Hinckley M, Hoffman MS, Papenfuss J, Hansen CB, Callis KP et al. Impact of obesity and smoking on psoriasis presentation and management. Arch Dermatol 2005; 141: 1527–1534.

Kaye JA, Li L, Jick SS . Incidence of risk factors for myocardial infarction and other vascular diseases in patients with psoriasis. Br J Dermatol 2008; 159: 895–902.

Langan SM, Seminara NM, Shin DB, Troxel AB, Kimmel SE, Mehta NN et al. Prevalence of metabolic syndrome in patients with psoriasis: a population-based study in the United Kingdom. J Invest Dermatol 2012; 132 (Part 1): 556–562.

Naldi L, Chatenoud L, Linder D, Belloni Fortina A, Peserico A, Virgili AR et al. Cigarette smoking, body mass index, and stressful life events as risk factors for psoriasis: results from an Italian case-control study. J Invest Dermatol 2005; 125: 61–67.

Neimann AL, Shin DB, Wang X, Margolis DJ, Troxel AB, Gelfand JM . Prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors in patients with psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol 2006; 55: 829–835.

Schmitt J, Ford DE . Psoriasis is independently associated with psychiatric morbidity and adverse cardiovascular risk factors, but not with cardiovascular events in a population-based sample. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2010; 24: 885–892.

Shapiro J, Cohen AD, Weitzman D, Tal R, David M . Psoriasis and cardiovascular risk factors: a case-control study on inpatients comparing psoriasis to dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol 2012; 66: 252–258.

Takahashi H, Takahashi I, Honma M, Ishida-Yamamoto A, Iizuka H . Prevalence of metabolic syndrome in Japanese psoriasis patients. J Dermatol Sci 2010; 57: 143–144.

Warnecke C, Manousaridis I, Herr R, Terris DD, Goebeler M, Goerdt S et al. Cardiovascular and metabolic risk profile in German patients with moderate and severe psoriasis: a case control study. Eur J Dermatol 2011; 21: 761–770.

Xiao J, Chen LH, Tu YT, Deng XH, Tao J . Prevalence of myocardial infarction in patients with psoriasis in central China. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2009; 23: 1311–1315.

Zhang C, Zhu KJ, Zheng HF, Cui Y, Zhou FS, Chen YL et al. The effect of overweight and obesity on psoriasis patients in Chinese Han population: a hospital-based study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2011; 25: 87–91.

Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC, Olkin I, Williamson GD, Rennie D et al. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. Meta-analysis Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) group. JAMA 2000; 283: 2008–2012.

Micha R, Wallace SK, Mozaffarian D . Red and processed meat consumption and risk of incident coronary heart disease, stroke, and diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Circulation 2010; 121: 2271–2283.

DerSimonian R, Laird N . Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials 1986; 7: 177–188.

Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C . Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ 1997; 315: 629–634.

Begg CB, Mazumdar M . Operating characteristics of a rank correlation test for publication bias. Biometrics 1994; 50: 1088–1101.

Guerre-Millo M . Adipose tissue and adipokines: for better or worse. Diabetes Metab 2004; 30: 13–19.

Ronti T, Lupattelli G, Mannarino E . The endocrine function of adipose tissue: an update. Clin Endocrinol 2006; 64: 355–365.

Schwartz MW, Woods SC, Porte D, Seeley RJ, Baskin DG . Central nervous system control of food intake. Nature 2000; 404: 661–671.

Ciccone M, Vettor R, Pannacciulli N, Minenna A, Bellacicco M, Rizzon P et al. Plasma leptin is independently associated with the intima-media thickness of the common carotid artery. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 2001; 25: 805–810.

Bodary PF, Westrick RJ, Wickenheiser KJ, Shen Y, Eitzman DT . Effect of leptin on arterial thrombosis following vascular injury in mice. JAMA 2002; 287: 1706–1709.

Chen YJ, Wu CY, Shen JL, Chu SY, Chen CK, Chang YT et al. Psoriasis independently associated with hyperleptinemia contributing to metabolic syndrome. Arch Dermatol 2008; 144: 1571–1575.

Takahashi H, Tsuji H, Takahashi I, Hashimoto Y, Ishida-Yamamoto A, Iizuka H . Plasma adiponectin and leptin levels in Japanese patients with psoriasis. Br J Dermatol 2008; 159: 1207–1208.

Coimbra S, Oliveira H, Reis F, Belo L, Rocha S, Quintanilha A et al. Circulating adipokine levels in Portuguese patients with psoriasis vulgaris according to body mass index, severity and therapy. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2010; 24: 1386–1394.

Okamoto Y, Kihara S, Funahashi T, Matsuzawa Y, Libby P . Adiponectin: a key adipocytokine in metabolic syndrome. Clin Sci 2006; 110: 267–278.

Florin V, Cottencin AC, Delaporte E, Staumont-Salle D . Body weight increment in patients treated with infliximab for plaque psoriasis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol e-pub ahead of print 23 May 2012; DOI: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2012.04571.x.

Renzo LD, Saraceno R, Schipani C, Rizzo M, Bianchi A, Noce A et al. Prospective assessment of body weight and body composition changes in patients with psoriasis receiving anti-TNF-alpha treatment. Dermatol Ther 2011; 24: 446–451.

Prignano F, Ricceri F, Pescitelli L, Buggiani G, Troiano M, Zanieri F et al. Comparison of body weight and clinical-parameter changes following the treatment of plaque psoriasis with biological therapies. Curr Med Res Opin 2009; 25: 2311–2316.

Saraceno R, Schipani C, Mazzotta A, Esposito M, Di Renzo L, De Lorenzo A et al. Effect of anti-tumor necrosis factor-alpha therapies on body mass index in patients with psoriasis. Pharmacol Res 2008; 57: 290–295.

Gisondi P, Cotena C, Tessari G, Girolomoni G . Anti-tumour necrosis factor-alpha therapy increases body weight in patients with chronic plaque psoriasis: a retrospective cohort study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2008; 22: 341–344.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Armstrong, A., Harskamp, C. & Armstrong, E. The association between psoriasis and obesity: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Nutr & Diabetes 2, e54 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1038/nutd.2012.26

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/nutd.2012.26

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Triggers for the onset and recurrence of psoriasis: a review and update

Cell Communication and Signaling (2024)

-

Investigating causal relationships between obesity and skin barrier function in a multi-ethnic Asian general population cohort

International Journal of Obesity (2023)

-

Comparative Effectiveness of Biologics Across Subgroups of Patients with Moderate-to-Severe Plaque Psoriasis: Results at Week 12 from the PSoHO Study in a Real-World Setting

Advances in Therapy (2023)

-

The differentiating effect of COVID-19-associated stress on the morbidity of blood donors with symptoms of hidradenitis suppurativa, hyperhidrosis, or psoriasis

Quality of Life Research (2023)

-

The Effectiveness of Guselkumab by BMI Category Among Patients with Moderate-to-Severe Plaque Psoriasis in the CorEvitas Psoriasis Registry

Advances in Therapy (2023)