Abstract

Summary

The effect of teriparatide and risedronate on back pain was tested, and there was no difference in the proportion of patients experiencing a reduction in back pain between groups after 6 or 18 months. Patients receiving teriparatide had greater increases in bone mineral density and had fewer vertebral fractures.

Introduction

This study aimed to understand the effect of teriparatide in reducing back pain in patients with prevalent back pain and vertebral fracture compared to risedronate.

Methods

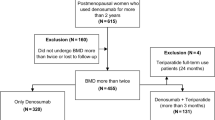

In an 18-month randomized, double-blind, double-dummy trial, we investigated the effects of teriparatide (20 μg/day) vs. risedronate (35 mg/week) in postmenopausal women with back pain likely due to vertebral fracture. The primary objective was to compare the proportion of subjects reporting ≥30% reduction in worst back pain severity from baseline to 6 months as assessed by a numeric rating scale in each treatment group. Pre-specified secondary and exploratory outcomes included assessments of average and worst back pain at additional time points, disability and quality of life, bone mineral density, incidence of fractures, and safety.

Results

At 6 months, 59% of teriparatide and 57% of risedronate patients reported ≥30% reduction in worst back pain and there were no differences between groups in the proportion of patients experiencing reduction in worst or average back pain at any time point, disability, or quality of life. There was a greater increase from baseline in bone mineral density at the lumbar spine (p = 0.001) and femoral neck (p = 0.02) with teriparatide compared to risedronate and a lower incidence of vertebral fractures at 18 months (4% teriparatide and 9% risedronate; p = 0.01). Vertebral fractures were less severe (p = 0.04) in the teriparatide group. There was no difference in the overall incidence of adverse events.

Conclusions

Although there were no differences in back pain-related endpoints, patients receiving teriparatide had greater skeletal benefit than those receiving risedronate.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Nevitt MC et al (1998) The association of radiographically detected vertebral fractures with back pain and function: a prospective study. Ann Intern Med 128:793–800

Ettinger B et al (1992) Contribution of vertebral deformities to chronic back pain and disability. The Study of Osteoporotic Fractures Research Group. J Bone Miner Res 7:449–456

Silverman SL, Minshall ME, Shen W, Harper KD, Xie S (2001) The relationship of health-related quality of life to prevalent and incident vertebral fractures in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis: results from the Multiple Outcomes of Raloxifene Evaluation Study. Arthritis Rheum 44:2611–2619

Gold DT (2001) The nonskeletal consequences of osteoporotic fractures. Psychologic and social outcomes. Rheum Dis Clin North Am 27:255–262

Silverman SL, Piziak VK, Chen P, Misurski DA, Wagman RB (2005) Relationship of health related quality of life to prevalent and new or worsening back pain in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis. J Rheumatol 32:2405–2409

Langdahl BL et al (2009) Reduction in fracture rate and back pain and increased quality of life in postmenopausal women treated with teriparatide: 18-month data from the European Forsteo Observational Study (EFOS). Calcif Tissue Int 85:484–493

Neer RM et al (2001) Effect of parathyroid hormone (1–34) on fractures and bone mineral density in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis. N Engl J Med 344:1434–1441

Lyritis G et al (2010) Back pain during different sequential treatment regimens of teriparatide: results from EUROFORS. Curr Med Res Opin 26:1799–1807

Fahrleitner-Pammer A et al (2010) Fracture rate and back pain during and after discontinuation of teriparatide: 36-month data from the European Forsteo Observational Study (EFOS). Osteoporos Int 22(10):2709–2719

Farrar JT, Young JP Jr, LaMoreaux L, Werth JL, Poole RM (2001) Clinical importance of changes in chronic pain intensity measured on an 11-point numerical pain rating scale. Pain 94:149–158

Dworkin RH et al (2008) Interpreting the clinical importance of treatment outcomes in chronic pain clinical trials: IMMPACT recommendations. J Pain 9:105–121

Ostelo RW et al (2008) Interpreting change scores for pain and functional status in low back pain: towards international consensus regarding minimal important change. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 33:90–94

Fechtenbaum J et al (2005) The severity of vertebral fractures and health-related quality of life in osteoporotic postmenopausal women. Osteoporos Int 16:2175–2179

Lips P et al (1999) Quality of life in patients with vertebral fractures: validation of the Quality of Life Questionnaire of the European Foundation for Osteoporosis (QUALEFFO). Working Party for Quality of Life of the European Foundation for Osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int 10:150–160

Genant HK, Wu CY, Van KC, Nevitt MC (1993) Vertebral fracture assessment using a semiquantitative technique. J Bone Miner Res 8:1137–1148

Looker AC et al (1997) Prevalence of low femoral bone density in older U.S. adults from NHANES III. J Bone Miner Res 12:1761–1768

Shipp KM et al (2000) Timed loaded standing: a measure of combined trunk and arm endurance suitable for people with vertebral osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int 11:914–922

Harden RN et al (2005) Medication Quantification Scale Version III: update in medication classes and revised detriment weights by survey of American Pain Society Physicians. J Pain 6:364–371

Minne H et al (2008) Bone density after teriparatide in patients with or without prior antiresorptive treatment: one-year results from the EUROFORS study. Curr Med Res Opin 24:3117–3128

Kallmes DF et al (2009) A randomized trial of vertebroplasty for osteoporotic spinal fractures. N Engl J Med 361:569–579

McClung MR et al (2005) Opposite bone remodeling effects of teriparatide and alendronate in increasing bone mass. Arch Intern Med 165:1762–1768

Saag KG et al (2007) Teriparatide or alendronate in glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis. N Engl J Med 357:2028–2039

Saag KG et al (2009) Effects of teriparatide versus alendronate for treating glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis: thirty-six-month results of a randomized, double-blind, controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum 60:3346–3355

Lindsay R et al (2009) Relationship between duration of teriparatide therapy and clinical outcomes in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int 20:943–948

Genant HK, Siris E, Crans GG, Desaiah D, Krege JH (2005) Reduction in vertebral fracture risk in teriparatide-treated postmenopausal women as assessed by spinal deformity index. Bone 37:170–174

Prevrhal S, Krege JH, Chen P, Genant H, Black DM (2009) Teriparatide vertebral fracture risk reduction determined by quantitative and qualitative radiographic assessment. Curr Med Res Opin 25:921–928

Black DM et al (1999) Defining incident vertebral deformity: a prospective comparison of several approaches. The Study of Osteoporotic Fractures Research Group. J Bone Miner Res 14:90–101

Pluijm SM, Tromp AM, Smit JH, Deeg DJ, Lips P (2000) Consequences of vertebral deformities in older men and women. J Bone Miner Res 15:1564–1572

Genant HK et al (2005) The effects of teriparatide on the incidence of back pain in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis. Curr Med Res Opin 21:1027–1034

Miller PD et al (2005) Longterm reduction of back pain risk in women with osteoporosis treated with teriparatide compared with alendronate. J Rheumatol 32:1556–1562

Nevitt MC et al (2006) Reduction in the risk of developing back pain persists at least 30 months after discontinuation of teriparatide treatment: a meta-analysis. Osteoporos Int 17:1630–1637

Nevitt MC et al (2006) Reduced risk of back pain following teriparatide treatment: a meta-analysis. Osteoporos Int 17:273–280

Bashutski JD et al (2010) Teriparatide and osseous regeneration in the oral cavity. N Engl J Med 363:2396–2405

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by Eli Lilly and Company. We thank Deborah Gold, Li Xie (Lilly employee and stockholder), Fernando Marin (Lilly employee and stockholder), and Donato Agnusdei (Lilly employee and stockholder) for their contributions to the study design; Sandra Walker (Lilly employee and stockholder), Erin Strouse (Lilly employee and stockholder), Valerie Ruff (Lilly employee and stockholder), Ewa Rogos (Lilly employee and stockholder), Beatriz Sans (Lilly employee and stockholder), Nadine Baker (Lilly employee and stockholder), and Joanne Lorraine (Lilly employee and stockholder) for their efforts in study management; and Mark Rohe (Lilly employee and stockholder), Hassan Jamal (Lilly employee and stockholder), David Shrom (Lilly employee and stockholder), and Gail Dalsky (Lilly employee and stockholder) for their technical assistance and writing support.

Contributing investigators include: Argentina: J.R. Zanchetta, Z. Man, E.M. Kerzberg, M.A. Lazaro, E.F. Mysler, and L. Naftal; Australia: A.P. Roberts, S. Hall, J. Eden, T. Diamond, and P. Nash; Belgium: S. Boonen, J.-M. Kaufman, Y. Bousten, M. Malaise, and M. De Meulemeester; Brazil: L. Russo, J. Neto, and R. Pereira; Canada: J. Adachi, A. Hodsman, R. Kremer, W.Olszynski, J.-L. Trembly, C. Yuen, D.L. Kendler, and J. Brown; France: C. Roux, M. De Vernejoul, P. Fardellone, L. Benhamou, F. Debiais, and C. Cormier; Germany: P. Hadji, F. Thomasius, J. Krug, P. Kaps, I. Frieling, C. Kasperk, C. Niedhart, and H. Radspieler; Italy: R. Nuti, S. Adami, and G. Resmini; Mexico: P. Garcia-Hernandez, J. Morales-Torres, J. Tamayo y Orozco, and R. Correa-Rotter; Spain: J. Del Pino, M. Munoz Torres, J. Roman Ivorra, C. Lozano Tonkin, M. Diaz Curiel, and E. Martin Mola; Sweden: O. Ljunggren, Y. Pernow, A. Ramnemark, and U.-B. Ericsson; USA: S. Broy, A. Myers, R. Leon, M. Econs, F. McKiernan, C. Recknor, T. Rooney, C. Ronkar, K. Saag, E. Schwartz, A. Sebba, O. Soto, G. Woodson, R. Feldman, J. Jakes, R. Recker, W. Saikali, J. Schechtman, N. Binkley, C. Deal, A. Abelson, L. Kohlmeier, and R. Sierra-Zorita.

Conflicts of interest

P. Hadji was a recipient of a grant/research support from Eli Lilly and Company, Procter & Gamble; speakers bureau with Eli Lilly and Company (Lilly) and Procter & Gamble; advisory board membership of Lilly and Procter & Gamble; consulting fees from Lilly and Procter & Gamble; lecture fees from Lilly and Procter & Gamble; and speaker fees from Lilly and Procter & Gamble.

J. Zanchetta received an advisory board membership of Lilly, Amgen, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, Pfizer, and Servier and consulting fees from Lilly, Amgen, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, Pfizer, and Servier.

C. Recknor received an advisory board membership of Lilly, Zelos, Takeda, and Novartis; consulting fees from Lilly, Zelos, Takeda, and Novartis; and lecture fees from Amgen and Novartis.

K. Saag was a recipient of a grant/research support from Lilly, Novartis, GlaxoSmithKline, Sanofi Aventis, and Procter & Gamble; speakers bureau with Novartis; and consulting fees from Lilly, Novartis, Merck, Procter & Gamble, Aventis, and Amgen.

F. McKiernan received consulting fees from Lilly and Amgen.

S. Silverman was a recipient of a grant/research support from Alliance for Better Bone Health, Lilly, Pfizer; speakers bureau with Amgen, Lilly, Pfizer, and Roche Pharmaceuticals; consulting fees from Amgen, Lilly, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche Pharmaceuticals, Roche Diagnostics, and Warner Chilcott.

J. Alam, R. Burge, J. Krege, M. Lakshmanan, D. Masica, B. Mitlak, and J. Stock were shareholders and employees of Lilly.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hadji, P., Zanchetta, J.R., Russo, L. et al. The effect of teriparatide compared with risedronate on reduction of back pain in postmenopausal women with osteoporotic vertebral fractures. Osteoporos Int 23, 2141–2150 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-011-1856-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-011-1856-y