Abstract

Summary

The risk of a subsequent major or any fracture after a hip fracture and secular trends herein were examined. Within 1 year, 2.7 and 8.4 % of patients sustained a major or any (non-hip) fracture, which increased to 14.7 and 32.5 % after 5 years. Subsequent fracture rates increased during the study period both for major and any (non-hip) fracture.

Introduction

Hip fractures are associated with subsequent fractures, particularly in the year following initial fracture. Age-adjusted hip fracture rates have stabilised in many developed countries, but secular trends in subsequent fracture remain poorly documented. We thus evaluated secular trends (2000–2010) and determinants for the risk of a subsequent major (humerus, vertebral, or forearm) and any (non-hip) fracture after hip fracture.

Methods

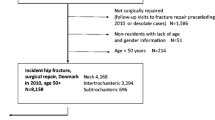

Patients ≥50 years with a hip fracture between 2000 and 2010 were extracted from the UK Clinical Practice Research Datalink (n = 30,516). Incidence rates, cumulative incidence probabilities, and adjusted hazard ratios (aHRs) were calculated.

Results

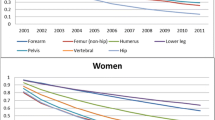

Within 1 year following hip fracture, 2.7 and 8.4 % of patients sustained a major or any (non-hip) fracture, which increased to 14.7 and 32.5 % after 5 years, respectively. The most important risk factors for a subsequent major fracture within 1 year were the female gender [aHR 1.90, 95 % confidence interval (CI) 1.51–2.40] and a history of secondary osteoporosis (aHR 1.54, 95 % CI 1.17–2.02). The annual risk increased during the study period for both subsequent major (2009–2010 vs. 2000–2002: aHR 1.44, 95 % CI 1.12–1.83) and any (non-hip) facture (2009–2010 vs. 2000–2002: aHR 1.80, 95 % CI 1.58–2.06).

Conclusion

The risk of sustaining a major or any (non-hip) fracture after hip fracture is small in the first year. However, given the recent rise in secondary fracture rates and the substantial risk of subsequent fracture in the longer term, fracture prevention is clearly indicated for patients who have sustained a hip fracture.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Lee YK, Lee YJ, Ha YC, Koo KH (2014) Five-year relative survival of patients with osteoporotic hip fracture. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 99:97–100

Bertran M, Norman R, Kemp L, Vos T (2011) Review of the long-term disability associated with hip fractures. Inj Prev 17:365–370

Ryg J, Rejnmark L, Overgaard S, Brixen K, Vestergaard P (2009) Hip fracture patients at risk of second hip fracture: a nationwide population-based cohort study of 169,145 cases during 1977–2001. J Bone Miner Res 24:1299–1307

Klotzbuecher CM, Ross PD, Landsman PB, Abbott TA 3rd, Berger M (2000) Patients with prior fractures have an increased risk of future fractures: a summary of the literature and statistical synthesis. J Bone Miner Res 15:721–739

Warriner AH, Patkar NM, Yun H, Delzell E (2012) Minor, major, low-trauma, and high-trauma fractures: what are the subsequent fracture risks and how do they vary? Curr Osteoporos Rep 10:22–27

Huntjens KM, Kosar S, van Geel TA, Geusens PP, Willems P, Kessels A, Brink P, van Helden S (2010) Risk of subsequent fracture and mortality within 5 years after a non-vertebral fracture. Osteoporos Int 21:2075–2082

Johnell O, Kanis JA, Odén A, Sernbo I, Redlund-Johnell I, Petterson C, De Laet C, Jönsson B (2004) Fracture risk following an osteoporotic fracture. Osteoporos Int 15:175–179

van Helden S, Cals J, Kessels F, Brink P, Dinant GJ, Geusens P (2006) Risk of new clinical fractures within 2 years following a fracture. Osteoporos Int 17:348–354

von Friesendorff M, Besjakov J, Akesson K (2008) Long-term survival and fracture risk after hip fracture: a 22-year follow-up in women. J Bone Miner Res 23:1832–1841

van Geel TA, van Helden S, Geusens PP, Winkens B, Dinant GJ (2009) Clinical subsequent fractures cluster in time after first fractures. Ann Rheum Dis 68:99–102

Sawalha S, Parker MJ (2012) Characteristics and outcome in patients sustaining a second contralateral fracture of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 94:102–106

Bliuc D, Nguyen ND, Milch VE, Nguyen TV, Eisman JA, Center JR (2009) Mortality risk associated with low-trauma osteoporotic fracture and subsequent fracture in men and women. JAMA 301:513–521

Pearse EO, Redfern DJ, Sinha M, Edge AJ (2003) Outcome following a second hip fracture. Injury 34:518–521

Cooper C, Cole ZA, Holroyd CR, Earl SC, Harvey NC, Dennison EM, Melton LJ, Cummings SR, Kanis JA (2011) Secular trends in the incidence of hip and other osteoporotic fractures. Osteoporos Int 22:1277–1288

Alves SM, Economou T, Oliveira C, Ribeiro AL, Neves N, Gomez-Barrena E, Pina MF (2013) Osteoporotic hip fractures: bisphosphonates sales and observed turning point in trend. A population based retrospective study. Bone 53:430–436

Turkington P, Madonald S, Elliott J, Beringer T (2012) Hip fracture in Northern Ireland, 1985–2010. Are age specific rates still rising? Ulster Med J 81:123–126

Melton LJ III, Therneau TM, Larson DR (1998) Long-term trends in hip fracture prevalence: the influence of hip fracture incidence and survival. Osteoporos Int 8:68–74

National Institute for Clinical Excellence (2005) Technology appraisal guidance 87 bisphosphonates (alendronate, etidronate, risedronate), selective oestrogen receptor modulators (raloxifene) and parathyroid hormone (teriparatide) for the secondary prevention of osteoporotic fragility fractures in postmenopausal women

Omsland TK, Holvik K, Meyer HE, Center JR, Emaus N, Tell GS, Schei B, Tverdal A, Gjesdal CG, Grimnes G, Forsmo S, Eisman JA, Søgaard AJ (2012) Hip fractures in Norway 1999–2008: time trends in total incidence and second hip fracture rates: a NOREPOS study. Eur J Epidemiol 27:807–814

Melton LJ 3rd, Kearns AE, Atkinson EJ, Bolander ME, Achenbach SJ, Huddleston JM, Therneau TM, Leibson CL (2009) Secular trends in hip fracture incidence and recurrence. Osteoporos Int 20:687–694

Kanis JA, Mc Closkey EV, Johansson H, Oden A, Ström O, Borgström F (2010) Development and use of FRAX in osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int 21:407–413

Van Staa TP, Abenhaim L, Cooper C, Zhang B, Leufkens HG (2000) The use of a large pharmacoepidemiological database to study exposure to oral corticosteroids and risk of fractures: validation of study population and results. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 9:359–366

Warriner A, Patkar N, Curtis J, Delzell E, Gary L, Kilgore M, Saag K (2011) Which fractures are most attributable to osteoporosis? J Clin Epidemiol 64:46–53

Ström O, Borgström F, Kanis JA, Compston J, Cooper C, McCloskey EV, Jönsson B (2011) Osteoporosis: burden, health care provision and opportunities in the EU. Arch Osteoporos 6:59–155

Egan M, Jaglal S, Byrne K, Wells J, Stolee P (2008) Factors associated with a second hip fracture: a systematic review. Clin Rehabil 22:272–282

Colón-Emeric CS, Lyles KW, Su G, Pieper CF, Magaziner JS, Adachi JD, Bucci-Rechtweg CM, Haentjens P, Boonen S (2011) Clinical risk factors for recurrent fracture after hip fracture: a prospective study. Calcif Tissue Int 88:425–431

Reid DM, Harvie J (1997) Secondary osteoporosis. Baillieres Clin Endocrinol Metab 11:83–91

Woolcott JC, Richardson KJ, Wiens MO, Patel B, Marin J, Khan KM, Marra CA (2009) Meta-analysis of the impact of 9 medication classes on falls in elderly persons. Arch Intern Med 169:1952–1960

Carbone LD, Johnson KC, Robbins J, Larson JC, Curb JD, Watson K, Gass M, Lacroix AZ (2010) Antiepileptic drug use, falls, fractures, and BMD in postmenopausal women: findings from the women's health initiative (WHI). J Bone Miner Res 25:873–881

Doggrell SA (2003) Present and future pharmocatherapy for osteoporosis. Drugs Today 39:633

Hagino H, Sawaguchi T, Endo N, Ito Y, Nakano T, Watanabe Y (2012) The risk of second hip fracture in patients after their first hip fracture. Calcif Tissue Int 90:14–21

Budicǎ CR, Cristea ŞT, Panait GH (2010) Risk assessment of new fracture following fragility hip fracture. Arch Balk Med Union 45:40–48

Curtis JR, Arora T, Matthews RS, Taylor A, Becker DJ, Colon-Emeric C, Kilgore ML, Morrisey MA, Saag KG, Safford MM, Warriner A, Delzell E (2010) Is withholding osteoporosis medication after fracture sometimes rational? A comparison of the risk for second fracture versus death. J Am Med Dir Assoc 11:584–591

Chen JS, Sambrook PN, Simpson JM, Cameron ID, Cumming RG, Seibel MJ et al (2009) Risk factors for hip fracture among institutionalised older people. Age Ageing 38:429–434

Thomas SL, Edwards CJ, Smeeth L, Cooper C, Hall AJ (2008) How accurate are diagnoses for rheumatoid arthritis and juvenile idiopathic arthritis in the general practice research database? Arthritis 59:1314–1321

Smith P, Ariti C, Bardsley M (2013) Focus on hip fracture: trends in emergency admission for fractured neck of femur, 2001 to 2011. Nuffield Trust/Health Foundation

The American Society for Bone and Mineral Research (2013) Annual meeting. http://www.asbmr.org/asbmr-2013-abstract-detail?aid=ff336fa6-534a-4a7b-b96a-63ee30d19fcb. Accessed 08 Jan 2014

Watson J, Wise L, Green J (2007) Prescribing hormone therapy for menopause, tibolone and bisphosphonates in women in the UK between 1991 and 2005. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 63:843–849

Cadarette SM, Katz JN, Brookhart MA, Levin R, Stedman MR, Choudhry NK, Solomon DH (2008) Trends in drug prescribing for osteoporosis after hip fracture, 1995–2004. J Rheumatol 35:319–326

Acknowledgment

This study was supported by a research grant from The Netherlands Organisation for Health Research and Development (ZonMw; grant number 113101007) and the UK National Osteoporosis Society. The funders had no role in study design, data collection, and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Conflicts of interest

This work was supported by a grant from The Netherlands Organisation for Health Research and Development. The Division of Pharmacoepidemiology & Clinical Pharmacology employing FV, CK, and TPS has received unrestricted funding from the Netherlands Organisation for Health Research and Development (ZonMW), the Dutch Health Care Insurance Board (CVZ), the Royal Dutch Pharmacists Association (KNMP), the private–public-funded Top Institute Pharma (http://www.tipharma.nl) including co-funding from universities, government, and industry, the EU Innovative Medicines Initiative (IMI), the EU 7th Framework Program (FP7), the Dutch Ministry of Health and industry (including GlaxoSmithKline, Pfizer, etc.). HGML is a researcher at The WHO Collaborating Centre for Pharmaceutical Policy & Regulation, which receives no direct funding or donations from private parties, including pharma industry. Research funding from public–private partnerships, e.g., IMI, TI Pharma (http://www.tipharma.nl) is accepted under the condition that no company-specific product or company-related study is conducted. The centre has received unrestricted research funding from public sources, e.g., the Netherlands Organisation for Health Research and Development (ZonMW), the Dutch Health Care Insurance Board (CVZ), the EU 7th Framework Program (FP7), the Dutch Medicines Evaluation Board (MEB), and the Dutch Ministry of Health. The authors DGS, PE, NS, PMJW, and NCH report no conflict of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Gibson-Smith, D., Klop, C., Elders, P.J.M. et al. The risk of major and any (non-hip) fragility fracture after hip fracture in the United Kingdom: 2000–2010. Osteoporos Int 25, 2555–2563 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-014-2799-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-014-2799-x