Abstract

Summary

Fractures after the age of 50 are frequently observed in Denmark, and many of these may be osteoporotic. This study examined the incidence of all and subsequent fractures in a 10-year period from 2001 to 2011. The incidence of subsequent fractures was high, especially following hip fracture.

Introduction

The purpose of this study is to examine patterns of subsequent fractures and mortality rates over a 10-year period in patients already suffering from fracture.

Methods

The study was designed as a nationwide, register-based follow-up study. Patients were included if diagnosed with an index fracture (ICD-10 codes: S22.x, S32.x, S42.x, S52.x, S62.x, S72.x, S82.x, S92.x, T02.x, T08.x, T10.x and T12.x) between January 1st, 2001 and December 31st, 2001 and if older than 50 years at time of fracture. The patients were investigated for future subsequent fractures from January 1st, 2002 to December 31st, 2011.

Results

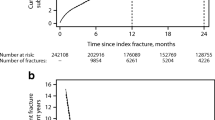

In this study, we demonstrated that patients with fractures (especially hip fractures) have a high risk of subsequent fractures, especially hip fracture. Other fractures, which are not commonly considered as osteoporotic fractures, such as lower leg, were frequently observed in the 10 years following index fracture. The cumulative incidence proportion (CIP) of subsequent fractures during the 10-year follow-up period was high for all recurrent fractures (9–46 %). Subsequent hip fracture, regardless of index fracture, had the highest CIP across the study period, ranging from 9 to 40 %. Appendicular fractures were often followed by a recurrent fracture, or subsequent fractures at a more proximal location in the same limb, i.e. forearm fractures were followed by humerus fractures. These results have not been previously demonstrated to this extent, and according to our knowledge, no previous studies have estimated cumulative 10-year subsequent fracture incidences for any non-hip fractures.

Conclusion

Patients suffering a fracture (and especially a hip fracture) have a high incidence of subsequent fracture. Fractures after the age of 50 may be considered an early warning of increased risk for future fractures in many patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Melton LJ III (1995) Epidemiology of fractures. In: Riggs B, Melton LJ III (eds) Osteoporosis: etiology, diagnosis, and management, Second edn. Lippincott-Raven, Philadelphia, pp 225–247

Kanis JA, Johnell O, Oden A et al (2002) Ten-year risk of osteoporotic fracture and the effect of risk factors on screening strategies. Bone 30:251–258

Warriner AH, Patkar NM, Curtis JR et al (2011) Which fractures are most attributable to osteoporosis? J Clin Epidemiol 64:46–53

Marshall DA, Johnell O, Wedel H (1996) Meta-analysis of how well measures of bone mineral density predict occurrence of osteoporotic fractures. BMJ 312:1254

Hansen L, Mathiesen AS, Vestergaard P et al (2013) A health economic analysis of osteoporotic fractures: who carries the burden? Arch Osteoporos 8:126

Abrahamsen B, Eiken P, Eastell R (2009) Subtrochanteric and diaphyseal femur fractures in patients treated with alendronate: a register-based national cohort study. J Bone Miner Res 24:1095–1102

Vestergaard P, Rejnmark L, Mosekilde L (2007) Increased mortality in patients with a hip fracture-effect of pre-morbid conditions and post-fracture complications. Osteoporos Int 18:1583–1593

Ryg J, Rejnmark L, Overgaard S et al (2009) Hip fracture patients at risk of second hip fracture: a nationwide population-based cohort study of 169,145 cases during 1977–2001. J Bone Miner Res 24:1299–1307

Borgström F, Zethraeus N, Johnell O et al (2006) Costs and quality of life associated with osteoporosis-related fractures in Sweden. Osteoporos Int 17:637–650. doi:10.1007/s00198-005-0015-8

World Health Organization Collaborating Centre for Metabolic Bone Diseases (2013) FRAX ® WHO fracture risk assessment tool. http://www.shef.ac.uk/FRAX/index.aspx. Accessed 14 Aug 2013

Garvan Institute (2013) Fracture risk calculator. http://www.garvan.org.au/bone-fracture-risk/. Accessed 22 Aug 2013

McLellan AR, Gallacher SJ, Fraser M, McQuillian C (2003) The fracture liaison service: success of a program for the evaluation and management of patients with osteoporotic fracture. Osteoporos Int 14:1028–1034

Brixen K, Overgaard S, Gram J et al (2012) Systematisk forebyggelse og behandling af knogleskørhed hos patienter med hoftebrud – en medicinsk teknologi vurdering

Chari S, McRae P, Varghese P et al (2013) Predictors of fracture from falls reported in hospital and residential care facilities: a cross-sectional study. BMJ 3:1–7

Bischoff-Ferrari HA (2011) The role of falls in fracture prediction. Curr Osteoporos Rep 9:116–121

Johansson C, Mellstrom D (1996) An earlier fracture as a risk factor for new fracture and its association with smoking and menopausal age in women. Maturitas 24:97–106

Gunnes M, Mellstrom D, Johnell O (1998) How well can a previous fracture indicate a new fracture? A questionnaire study of 29,802 postmenopausal women. Acta Orthop Scand 69:508–512

Klotzbuecher CM, Ross PD, Landsman PB et al (2000) Patients with prior fractures have an increased risk of future fractures: a summary of the literature and statistical synthesis. J Bone Miner Res 15:721–739

Frank L (2000) When an entire country is a cohort. Science 287(80-):2398–2399

Andersen T, Madsen M, Jørgensen J et al (1999) The Danish National Hospital Register. A valuable source of data for modern health sciences. Dan Med Bull J Health Sci 46:263–268

Mosbech J, Jørgensen J, Madsen M et al (1995) The national patient registry. Evaluation of data quality. Ugeskr Laeger 157:3741–3745

Vestergaard P, Mosekilde L (2002) Fracture risk in patients with celiac disease, Crohn’s disease, and ulcerative colitis: a nationwide follow-up study of 16, 416 patients in Denmark. Am J Epidemiol 156:8–10

Von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M et al (2008) The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. J Clin Epidemiol 61:344–349

Statistics Denmark (2013) StatBank Denmark. Population and elections

Kannegaard PN, van der Mark S, Eiken P, Abrahamsen B (2010) Excess mortality in men compared with women following a hip fracture. National analysis of comedications, comorbidity and survival. Age Ageing 39:203–209

Hodsman AB, Leslie WD, Tsang JF, Gamble GD (2008) 10-year probability of recurrent fractures following wrist and other osteoporotic fractures in a large clinical cohort. Arch Intern Med 168:2261–2267

Omsland TK, Emaus N, Tell GS et al (2013) Ten-year risk of second hip fracture. A NOREPOS study. Bone 52:493–497

Port L, Center J, Briffa NK et al (2003) Osteoporotic fracture: missed opportunity for intervention. Osteoporos Int 14:780–784

Edwards B, Bunta A, Simonelli C et al (2007) Prior fractures are common in patients with subsequent hip fractures. Clin Orthop Relat Res 461:226–230

Eisman JA, Bogoch ER, Dell R et al (2012) Making the first fracture the last fracture: ASBMR task force report on secondary fracture prevention. J Bone Miner Res 27:2039–2046

Ryg J (2009) Ph.d. Thesis: osteoporose og hoftebrud – en klinisk, økonomisk og epidemiologisk undersøgelse

Harris ST, Watts NB, Genant HK et al (1999) Effects of risedronate treatment on vertebral and nonvertebral fractures in women with postmenopausal osteoporosis: a randomized controlled trial. Vertebral Efficacy With Risedronate Therapy (VERT) Study Group. J Am Med Assoc 282:1344–1352

Chesnut CH III, Skag A, Christiansen C et al (2004) Effects of oral ibandronate administered daily or intermittently on fracture risk in postmenopausal osteoporosis. J Bone Miner Res 19:1241–1249

Reginster JY, Seeman E, De Vernejoul MC et al (2005) Strontium ranelate reduces the risk of nonvertebral fractures in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis: Treatment of Peripheral Osteoporosis (TROPOS) study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 90:2816–2822

Amin S, Achenbach SJ, Atkinson EJ et al (2014) Trends in fracture incidence: a population-based study over 20 years. J Bone Miner Res 29:581–589. doi:10.1002/jbmr.2072

Abrahamsen B, Vestergaard P (2010) Declining incidence of hip fractures and the extent of use of anti-osteoporotic therapy in Denmark 1997–2006. Osteoporos Int 21:373–380

Ankjaer-Jensen A, Johnell O (1996) Prevention of osteoporosis: cost-effectiveness of different pharmaceutical treatments. Osteoporos Int 6:265–275

Funding

This study was supported by a grant from the Danish Bone Society.

Conflicts of interest

LH has received research grants from MSD Danmark ApS and honoraria from Eli Lilly and MSD Danmark.

KDP and SAE have no conflicts of interest.

BLL has received research grants from Eli Lilly and Axellus; served on advisory boards for Eli Lilly, Merck, Sharp & Dohme and Amgen and received honoraria from Eli Lilly, Merck, Sharp & Dohme and Amgen.

PE is an advisory board member of Eli Lilly, MSD and Amgen and has received lecture fees from Eli Lilly, Amgen and GlaxoSmithKline.

KB reports serving on the board for Osteologix, Servier, Amgen and Novartis; receiving payment for expert testimony on a patent for strontium maleate in the USA; consulting fees from Osteologix; lecture fees from Servier, Amgen, GlaxoSmithKline and Novartis and payment for travel accommodation from Amgen, Eli Lilly, Servier and Novartis.

KB further reports receiving grant support to his institution, Odense University Hospital, from Merck, Sharp & Dohme and Novartis and investigator payments from Merck, Sharp & Dohme, Osteologix, Servier, Amgen, Natural Product Sciences Pharmaceuticals and Eli Lilly.

BA received grants from or conducted trials for Novartis, Nycomed/Takeda and Amgen and served as an advisory board member for Nycomed/Takeda, Merck and Amgen.

JEBJ received honoraria from and is an advisory board member for Eli Lilly, Merck, Sharp & Dohme and Amgen.

TH received speaker’s honorarium from Amgen.

PV received unrestricted research grants from Servier and MSD and travel grants from Amgen, MSD, Eli Lilly, Novartis and Servier.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary material - Tables A-H

(DOCX 45 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hansen, L., Petersen, K.D., Eriksen, S.A. et al. Subsequent fracture rates in a nationwide population-based cohort study with a 10-year perspective. Osteoporos Int 26, 513–519 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-014-2875-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-014-2875-2