Abstract

Summary

The objectives of this study were to estimate persistence with denosumab and put these results in context by conducting a review of persistence with oral bisphosphonates. Persistence with denosumab was found to be higher than with oral bisphosphonates.

Purpose

This study had two objectives: to analyse persistence in Swedish women initiating denosumab for treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis (PMO) and to put these findings in context by conducting a literature review and meta-analysis of persistence data for oral bisphosphonates.

Methods

The study used the Swedish Prescribed Drug Register and included women aged at least 50 years initiating denosumab between May 2010 and July 2012. One injection of denosumab was defined as 6-month persistence. Women were considered persistent for another 6 months if they filled their next prescription within 6 months + 56 days and survival analysis applied to the data. A literature search was conducted in PubMed to identify retrospective studies of persistence with oral bisphosphonates and pooled persistence estimates were calculated using a random-effects model.

Results

The study identified 2,315 women who were incident denosumab users. Mean age was 74 years and 61 % had been previously treated for PMO. At 12 and 24 months, persistence with denosumab was 83 % (95 % CI, 81–84 %) and 62 % (95 % CI, 60–65 %), respectively. The literature search identified 40 articles for inclusion in the meta-analysis. At 12 and 24 months, persistence with oral bisphosphonates ranged from 10 % to 78 % and from 16 % to 46 %, with pooled estimates of 45 % and 30 %, respectively.

Conclusion

These data from the Swedish Prescribed Drug Register and literature review suggest that persistence was higher with denosumab than with oral bisphosphonates.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Osteoporosis is a disease characterized by excessive bone resorption leading to reduced bone strength and an increased risk of fracture. In women, reduced oestrogen levels during or after menopause can lead to postmenopausal osteoporosis (PMO) [1].

There are several treatments available for osteoporosis, which have the primary aim of reducing the risk of fracture [2, 3]. For optimal outcomes, patients need to take their treatment according to the dosing instructions and for the prescribed duration (i.e., they need to be both compliant and persistent with therapy) [4]. Studies in both the USA and Europe have shown that persistence with osteoporosis treatment is important for reducing the risk of fracture [5–7]. The data indicate that, compared with treatment lasting for less than 1-month, treatment must extend beyond 1 year in order to significantly reduce 3-year fracture incidence [6]. Evidence suggests, however, that approximately 50 % of women do not follow their prescribed osteoporosis treatment regimen and 50 % discontinue treatment within 1 year [8, 9]. Hence, persistence is an important consideration in the overall management of patients with osteoporosis. Moreover, modelling studies have shown that the incorporation of persistence in health economic evaluations can have a considerable impact on the estimated cost-effectiveness of an intervention [10, 11].

Oral bisphosphonates (BPs), including both alendronate and risedronate, are the current mainstay of anti-osteoporosis treatment in Europe [12]. Oral BPs can be administered daily, weekly, or monthly. An alternative treatment option is denosumab, a fully human monoclonal antibody that inhibits the RANK ligand, which is administered as a 60-mg subcutaneous injection once every 6 months. Denosumab 60 mg is indicated for the treatment of osteoporosis in postmenopausal women and in men at increased risk of fracture, and for the treatment of bone loss associated with hormone ablation in men with prostate cancer at increased risk of fracture [13]. Denosumab 60 mg has also been shown to increase bone mass in women with bone loss associated with adjuvant aromatase inhibitor therapy [14].

In patients with osteoporosis, the long-interval subcutaneous dosing regimen of denosumab could enable higher persistence with therapy than that observed with other anti-osteoporosis treatments [7, 9]. Indeed, levels of 12-month persistence have been reported with denosumab that vastly exceed the 50 % rate cited above. In a randomized, cross-over trial comparing denosumab with alendronate, 91 % of patients were persistent with treatment over 12 months, whilst in two single-arm, prospective, observational studies conducted in the USA, Canada, Austria, Belgium, Greece, and Germany, 12-month persistence rates varied from 82 to 94 % across countries [15–17]. To our knowledge, however, no study of real-world persistence with denosumab therapy in Sweden has yet been published.

This study had two objectives. The first was to estimate persistence in Swedish women in whom denosumab treatment was initiated for PMO and to explore patient characteristics that might affect persistence. The second was to put the findings regarding persistence with denosumab into context by conducting a literature review and meta-analysis of published, retrospective data on persistence with oral BPs.

Methods

Persistence with denosumab

Data source and patient selection

This study involved the analysis of data from the Swedish Prescribed Drug Register, which contains information on drugs dispensed on prescription since 2005 for the Swedish population (approximately 9.6 million individuals) [18]. Mortality data were collected from the Swedish Causes of Death Register, which includes death dates for all people residing in Sweden at the time of death. Swedish national registers have a high degree of accuracy. The loss of patient information from the Swedish Prescribed Drug Register is less than 0.6 % of all possible values and fewer than 0.5 % of all deaths are missing from the Causes of Death Register [19].

Women aged 50 years or older in whom denosumab treatment was initiated between 1 May 2010 and 31 July 2012 were identified in the Swedish Prescribed Drug Register. To capture relevant baseline characteristics, data needed to be available for at least the 18-month period before treatment initiation (the pre-index period). Similarly, to accumulate sufficient follow-up time to study persistence, data needed to be available for at least the 8-month period immediately following treatment initiation. The analysis focused on women with PMO and included only those receiving denosumab 60 mg. As denosumab is also used to increase bone mass in patients with bone loss associated with adjuvant aromatase inhibitor therapy, patients filling prescriptions for aromatase inhibitors in the pre-index period were excluded from the study.

Definition of persistence

Persistence was defined as the number of days from the date of treatment initiation to the end of the duration of the last filled prescription or the end of the study period (31 March 2013). One injection of denosumab equated to 6 months’ persistence; hence, all women were defined as being persistent with therapy for at least 6 months. Women were considered to be persistent for an additional 6 months if they filled their next denosumab prescription within 6 months + 56 days of administration of the previous injection (i.e., a gap of 56 days was permitted) [4]. Women failing to refill their prescription before the end of the permissible gap were defined as being non-persistent 6 months after the last filled prescription.

Covariates

The covariates used in the analysis were: age; previous osteoporosis treatment in the pre-index period; glucocorticoid use, defined as filling a prescription for cortisone, hydrocortisone, methylprednisolone, prednisolone, prednisone, triamcinolone, betamethasone, or dexamethasone equivalent to at least 450 mg of prednisolone in the pre-index period [20]; concurrent calcium and/or vitamin D supplementation, defined as filling prescriptions corresponding to at least 109,500 mg of calcium (1,200 mg/day for 3 months) and/or 73,000 IU of vitamin D (800 IU/day for 3 months) in the 6 months after treatment was initiated [21]; dependency, defined as living in a dependent/institutionalized setting (determined on the basis of the initial prescription being pre-dispensed); and receiving primary care (defined as the initial prescription being prescribed in the primary care setting).

Statistical analyses

Persistence with therapy was estimated at 12, 18, and 24 months using Kaplan–Meier survival curves, with non-persistence as the failure event. Women were censored for death and end of data availability (31 March 2013). Covariates associated with non-persistence were investigated using a parametric proportional hazards model (Weibull distribution).

The effects of alternative permissible gaps of 30, 90, and 180 days were explored using sensitivity analyses. Denosumab has a biannual dosing regimen and women may refill their prescriptions several months earlier than the date on which the next injection is needed, which can result in long gaps between prescriptions. This possible accumulation of denosumab was accounted for in another sensitivity analysis, which used a 56-day permissible gap and permitted women to cover future gaps between filled prescriptions with previously dispensed medication.

Subgroup analyses were conducted according to the calendar year of the index denosumab injection. Further subgroup analyses compared persistence in treatment-naïve women with that in treatment-experienced women. The latter group was defined as those with a prescription for another anti-osteoporosis drug (alendronate, risedronate, ibandronate, etidronate, zoledronic acid, strontium ranelate, raloxifene, or parathyroid hormone analogue) in the pre-index period.

Model distribution and covariate selection were based on maximizing the log-likelihood and minimizing the Akaike information criterion. The proportional hazards assumption was tested by graphical inspection and by exploring whether the included covariates significantly varied over time. The statistical analysis was executed using Stata 12 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA).

Persistence with oral bisphosphonates

Literature review

The literature review focused on persistence with oral BPs, which are the most commonly used treatments for osteoporosis in Europe and the USA [1]. Retrospective studies that estimated treatment persistence with oral BPs at 12 and 24 months were identified in the PubMed database. The search string used was “osteoporo*[All fields] AND (persistence[All fields] OR adherence[All fields] OR compliance[All fields] OR discontin*[All fields]) AND (register*[All fields] OR claim*[All fields] OR record*[All fields] OR health plan*[All fields] OR pharmacy*[All fields] OR prescript*[All fields]) OR (osteoporosis[All fields] AND persistence[All fields])”. Searches also included the MeSH terms “patient compliance”, “compliance”, “postmenopausal”, and “osteoporosis”. The search encompassed all articles published until 22 November 2013 with an English-language abstract.

In addition to the PubMed database search, seven review articles [22–28] were cited in the papers included after the literature search and full-text review. These review articles were manually searched to identify articles not found using the search string. To be included in this study, an article needed to present at least one estimate of 12- and 24-month persistence with oral BP treatment. No additional inclusion criteria were used.

Statistical analyses

Pooled estimates of persistence at 12 and 24 months were calculated using a random-effects model [29]. Subgroup analyses of 12-month persistence were conducted according to frequency of administration (weekly and daily; only for those studies directly comparing these two frequencies) and region (Europe, North America, and other).

Results

Persistence with denosumab

Study population

The final cohort consisted of 2,315 incident users of denosumab (Fig. 1) who contributed a total of 2,747 person-years. Baseline patient characteristics are presented in Table 1. Women were followed up for a mean (median) of 433 (387) days, until censoring or non-persistence with therapy. The majority (61 %) of women had received another anti-osteoporosis treatment in the 18 months before starting denosumab treatment. Approximately two fifths of women were prescribed their initial prescription medication in a primary care setting, and approximately one fifth had received glucocorticoids before initiation of denosumab treatment. Even though the inclusion period continued to 31 July 2012, the majority (62 %) of women filled their index prescription in 2010 or 2011.

Persistence

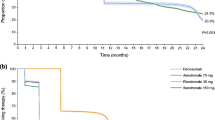

The estimated Kaplan–Meier curves for persistence with denosumab are presented in Fig. 2. Using a permissible gap of 56 days, persistence with denosumab treatment was 83 % (95 % CI, 81–84 %) at 12 months, 69 % (95 % CI, 67–71 %) at 18 months, and 62 % (95 % CI, 60–65 %) at 24 months. Increasing the permissible gap to 90 and 180 days, 12-month persistence was 84 % (95 % CI, 83–86 %) and 87 % (95 % CI, 86–88 %), respectively. Decreasing the permissible gap to 30 days, 12-month persistence was 78 % (95 % CI, 76–79 %).

The sensitivity analysis allowing patients to have overlapping prescriptions showed results similar to the analysis with a permissible gap of 90 days (data not shown).

At 24 months, women who had received previous anti-osteoporosis treatment (during the pre-index period) were more likely to be persistent with therapy than those who had not (65 vs. 58 %, p < 0.001); no difference was observed at 12 months (p = 1.000). No difference in 12-month persistence was found between women whose denosumab treatment was initiated in 2010 or 2011 and those first receiving denosumab in 2012 (p = 1.000).

Determinants of non-persistence

A multivariate Weibull model was fitted to identify variables that were significantly associated with non-persistence (Table 2). For all included covariates, no significant evidence of non-proportional hazards was observed (data not shown). Previous anti-osteoporosis treatment (during the pre-index period) was associated with a higher rate of persistence compared with no previous treatment. Filling a prescription for calcium and vitamin D supplementation in the first 6 months after denosumab initiation was also found to be associated with a higher persistence rate. Glucocorticoid treatment during the pre-index period was associated with a lower denosumab persistence rate. Age, pre-dispensing of the initial prescription, and receiving treatment in the primary care setting did not have significant effects on persistence levels.

Literature review and meta-analysis: persistence with oral bisphosphonates

Included articles

The search of the PubMed database identified 663 articles, most of which were excluded on the basis of their title or abstract (Fig. 3). The most frequent reasons for exclusion were: not reporting an estimate of 12- or 24-month persistence; discussing only hormone replacement therapy, osteoporotic fractures, or calcium/vitamin D supplementation; not using retrospective data; not having been written in English; and being a review. Review articles were manually searched for any articles that had not been identified by the search of PubMed [22, 28].

In total, 40 articles were included in the final review and meta-analysis (Table 3) [5, 6, 30–67]. These included studies from 12 different countries, with the largest number of studies being conducted in the USA (17 studies) [5, 35–38, 41, 42, 46, 49–51, 54, 56, 59, 63, 64, 66] and the next largest number being conducted in the Netherlands (four studies) [43, 44, 48, 61]. Two studies used the Swedish Prescribed Drug Register [6, 47]. In the majority of studies, a patient was defined as non-persistent with treatment if the time period between two consecutive prescription fills exceeded the length of the permissible gap. The most commonly used permissible gap was 30 days [5, 30, 32–40, 44, 49, 52, 55, 56, 58, 61, 65]; other commonly used permissible gaps were 60 and 90 days. In nine studies [6, 31, 40–42, 45, 47, 64, 66], patients were allowed to accumulate medicine (i.e., use supply from a previous prescription) and in 16 studies [6, 30–32, 34, 39, 40, 44–46, 52, 54, 55, 57, 61, 63], they were allowed to switch between treatments during the study period (e.g., from alendronate to risedronate or from weekly to daily oral BPs). The studies varied in the type of data source used (e.g., claims, medical charts), type of patients included (e.g., women with PMO, treatment-naïve women), and type of oral BP prescribed (e.g., alendronate, risedronate).

Persistence at 12 and 24 months

Of the 40 included studies, 39 reported at least one estimate of 12-month persistence with treatment (Fig. 4) [6, 30–67] and 17 [5, 6, 31, 32, 37, 45, 46, 48, 50–52, 55, 58, 59, 61, 64, 65] reported at least one estimate of 24-month persistence (Table 3). Estimates of 12-month persistence varied widely, from 10 to 78 %, with the majority of estimates ranging from 30 to 60 %, and there was a large amount of heterogeneity between studies in the methods used (Fig. 4). The pooled estimate of 12-month persistence with oral BP therapy was 45 % (95 % CI, 41–49 %). Estimates of 24-month persistence ranged from 16 to 46 % (Table 3), and the pooled estimate was 30 % (95 % CI, 25–35 %). In Sweden, 12-month persistence with oral BPs was reported to be 51 % [6], and 52 % (in patients starting treatment in 2009) or 67 % (in those starting treatment in 2006) [47], and 24-month persistence reported to be 25 % [6] (Table 3).

Estimates of 12-month persistence with oral bisphosphonate treatment black square individual study, black diamond pooled estimate. Data are given as percentage (95 % confidence interval. Citation numbers of the studies detailed in this figure are given in Table 3

Studies investigating the differences between daily and weekly oral BPs [30, 35–37, 50, 55] reported that daily administration was associated with lower 12-month persistence compared with weekly administration (pooled estimates: 36 vs. 48 %, respectively) (Fig. 4). North American studies had a slightly lower pooled estimate of 12-month persistence compared with European studies (43 % based on 19 studies vs. 46 % based on 16 studies) (Fig. 4). The pooled 12-month estimate of persistence in other regions (based on four studies) was higher than the European and North American estimates. The results of studies varying the permissible gap all indicated that wider permissible gaps were associated with higher persistence with treatment [6, 31, 33, 41, 45, 49, 51, 63, 64, 66].

Discussion

For optimal clinical outcomes, women with PMO need to persist with anti-osteoporosis medications for the prescribed treatment duration. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first retrospective register study of persistence among Swedish women in whom denosumab therapy was initiated for the treatment of PMO. Twelve-month persistence with denosumab treatment was 83 %. This result is similar to previously reported estimates of persistence with denosumab [15–17] and is higher than previously published estimates of persistence with oral BPs. Indeed, this study’s pooled estimate from 39 studies of oral BPs showed that only 45 % of patients were persistent with treatment after 12 months.

Persistence with denosumab

The women included in our database study were slightly older than those included in a study of treatment-naïve users of oral BPs which also used the same database [6, 47]. Additionally, the majority of women in our study had previously received other anti-osteoporosis therapies; this is not surprising given that most women are prescribed oral BPs as their first line of treatment and subsequently switch to another treatment if they do not respond or experience intolerable side effects or dosing inconvenience. We estimated 12- and 24-month persistence with denosumab therapy to be 83 and 62 %, respectively, using a permissible gap of 56 days (8 weeks). The length of this gap is somewhat arbitrary and was chosen to be consistent with that used in previous studies of persistence using the same database [6, 47]. Varying the permissible gap to 30, 90, and 180 days resulted in estimated persistence rates of 78, 84, and 87 %, respectively, at 12 months, indicating that the estimates were robust.

Women who had received previous anti-osteoporosis therapies were more likely to persist with denosumab than treatment-naïve women. One possible explanation for this finding is that treatment-experienced women are more informed about their disease and receive more information from their prescriber. Filling a prescription for calcium and/or vitamin D supplementation in the first 6 months after initiating denosumab was significantly associated with persistence, with those who filled prescriptions having a higher persistence rate than those who did not. Similar results were reported by Cotte et al. [33], who found that the rate of persistence was higher in women taking calcium and vitamin D supplementation than in those who did not take such supplements. While the reason for this is not clear, a possible explanation is that calcium and vitamin D supplementation is an indicator of high risk and, therefore, high disease awareness. Finally, women receiving glucocorticoids before initiating denosumab had lower rates of persistence than those who had no experience of glucocorticoids. Similar results have been reported elsewhere for other anti-osteoporosis treatments [6, 44, 53], and further study is warranted to elucidate the reasons for the association between persistence and glucocorticoid use.

Persistence with oral bisphosphonates

The literature review identified 40 retrospective studies reporting at least one estimate of 12- or 24-month persistence with oral BPs, using varying methodologies. While all studies were similar in terms of how persistence was defined, they varied in the size of the permissible gap, which is directly related to the probability of being defined as non-persistent. Other study design heterogeneities concerned the possibility of a patient accumulating prescriptions or switching between dosages, dosing intervals, types of BP, and differences in study population. Less obvious differences, which were not systematically captured in our review, related to data quality and completeness, under-reporting by family physicians, and administrative hurdles. As well as methodological heterogeneity, the results are likely to have been influenced by other factors, such as types of healthcare organization, approaches to patient monitoring, drug reimbursement levels, and population disease awareness.

The pooled estimate from our literature review showed that 45 % of patients were persistent with oral BP therapy after 12 months. This relatively low persistence can possibly be explained by the asymptomatic nature of osteoporosis [68] and the complicated administration of oral BPs, whereby the tablet is taken under fasting conditions and with the patient remaining in an upright position for about an hour to avoid oesophageal reflux and oesophagitis, which, although infrequent, has been reported [69].

The two Swedish studies identified in the literature review were based on the Swedish Prescribed Drug Register. They estimated 12-month persistence with oral BPs to be 51 and 67 %, and 24-month persistence to be 25 % [6, 47]. It is worth noting that the estimate of 67 % was derived before the introduction of generic alendronate, which is likely to have caused a drop in persistence. These estimates for persistence with oral BP therapy are lower than the rates observed with denosumab using the same database. The permissible gap was identical to that in the present study (56 days); the only major difference was that patients were allowed to accumulate medicine in the studies of oral BPs.

Limitations

While retrospective register studies are based on historical prescription data and, hence, avoid the reporting bias that can arise in prospective studies, pharmaceuticals administered in hospitals are not captured by the Swedish Prescribed Drug Register and thus have not been included in our analysis. It is estimated that less than 10 % of sold denosumab doses have been administered in hospitals. By not including denosumab administered in hospitals, we may have not identified women who started treatment earlier than was recorded in the database and so we may have underestimated the true persistence rate; however, these women may be atypical and, to a large extent, may have been given denosumab for reasons related to cancer diagnoses. A register of prescriptions does not provide any assurance that the dose was actually taken; therefore, persistence with denosumab may have been overestimated in this study. Another limitation of retrospective data is that all variables of interest may not be available, and it was not possible in this database analysis to control for bone mineral density, concomitant medicine use, comorbidities, lifestyle factors, and socioeconomic variables, all of which may be important predictors of persistence [57].

The literature review included all identified retrospective studies on oral BPs that reported at least one estimate of either 12- or 24-month persistence, with no other quality requirement for inclusion. Some persistence estimates may consequently have been derived from data of insufficient quality for a robust analysis. In addition, there was heterogeneity between the studies. With this in mind, the pooled estimates and the comparisons between the studies need to be interpreted with some caution. Moreover, the analysis did not consider persistence with other anti-osteoporosis drugs such as zoledronic acid and intravenous bisphosphonates. Persistence with these treatments, which are administered less frequently than oral BPs, has previously been shown to be higher than with oral BPs [62].

Conclusion

Persistence with denosumab in women with PMO in Sweden was found to be approximately two-fold higher than pooled persistence rates from a meta-analysis of retrospective data on oral BPs. Our results from clinical practice are consistent with previous reports of persistence with denosumab, in both a clinical trial setting and studies of routine practice.

References

Kanis JA, McCloskey EV, Johansson H, Cooper C, Rizzoli R, Reginster JY, Scientific Advisory Board of the European Society for Clinical and Economic Aspects of Osteoporosis and Osteoarthritis (ESCEO), The Committee of Scientific Advisors of the International Osteoporosis Foundation (IOF) (2013) European guidance for the diagnosis and management of osteoporosis in postmenopausal women. Osteoporos Int 24:23–57

Eastell R (1998) Treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis. N Engl J Med 338:736–746

Giusti A, Bianchi G (2015) Treatment of primary osteoporosis in men. Clin Interv Aging 10:105–115

Cramer JA, Roy A, Burrell A, Fairchild CJ, Fuldeore MJ, Ollendorf DA, Wong PK (2008) Medication compliance and persistence: terminology and definitions. Value Health 11:44–47

Siris ES, Harris ST, Rosen CJ, Barr CE, Arvesen JN, Abbott TA, Silverman S (2006) Adherence to bisphosphonate therapy and fracture rates in osteoporotic women: relationship to vertebral and nonvertebral fractures from 2 US claims databases. Mayo Clin Proc 81:1013–1022

Landfeldt E, Ström O, Robbins S, Borgstrom F (2012) Adherence to treatment of primary osteoporosis and its association to fractures—the Swedish Adherence Register Analysis (SARA). Osteoporos Int 23:433–443

Lakatos P, Toth E, Cina Z, Lang Z, Psachoulia E, Intorcia M (2013) Persistence and compliance to treatment for osteoporosis in postmenopausal women in Hungary: A retrospective cohort study. Poster presented at the ISPOR 16th Annual European Congress, 2013, Dublin, Ireland, Poster ID: 34654

Compston JE, Seeman E (2006) Compliance with osteoporosis therapy is the weakest link. Lancet 368:973–974

Ström O, Borgstrom F, Kanis JA, Compston J, Cooper C, McCloskey EV, Jonsson B (2011) Osteoporosis: burden, health care provision and opportunities in the EU: a report prepared in collaboration with the International Osteoporosis Foundation (IOF) and the European Federation of Pharmaceutical Industry Associations (EFPIA). Arch Osteoporos 6:59–155

Jonsson B, Ström O, Eisman JA, Papaioannou A, Siris ES, Tosteson A, Kanis JA (2011) Cost-effectiveness of denosumab for the treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int 22:967–982

Hiligsmann M, Boonen A, Rabenda V, Reginster JY (2012) The importance of integrating medication adherence into pharmacoeconomic analyses: the example of osteoporosis. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res 12:159–166

Hernlund E, Svedbom A, Ivergard M, Compston J, Cooper C, Stenmark J, McCloskey EV, Jonsson B, Kanis JA (2013) Osteoporosis in the European Union: medical management, epidemiology and economic burden. A report prepared in collaboration with the International Osteoporosis Foundation (IOF) and the European Federation of Pharmaceutical Industry Associations (EFPIA). Arch Osteoporos 8:136

Prolia: EPAR - Product information (2014) http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/EPAR_-_Product_Information/human/001120/WC500093526.pdf (Accessed 30 September 2014)

Gnant M, Pfeiler G, Dubsky PC, Hubalek M, Greil R, Jakesz R, Wette V, Balic M, Haslbauer F, Melbinger E et al (2015) Adjuvant denosumab in breast cancer (ABCSG-18): a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60995-3

Freemantle N, Satram-Hoang S, Tang ET, Kaur P, Macarios D, Siddhanti S, Borenstein J, Kendler DL (2012) Final results of the DAPS (Denosumab Adherence Preference Satisfaction) study: a 24-month, randomized, crossover comparison with alendronate in postmenopausal women. Osteoporos Int 23:317–372

Silverman SL, Siris E, Kendler DL, Belazi D, Brown JP, Gold DT, Lewiecki EM, Papaioannou A, Simonelli C, Ferreira I et al (2015) Persistence at 12 months with denosumab in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis: interim results from a prospective observational study. Osteoporos Int 26:361–372

Hadji P, Papaioannou N, Gielen E, Tepie M, Zhang E, Frieling P, Geusens P, Makras P, Resch H, Möller G et al (2015) Persistence, adherence, and medication-taking behavior in women with postmenopausal osteoporosis receiving denosumab in routine practice in Germany, Austria, Greece, and Belgium: 12-month results from a European non-interventional study. Osteoporos Int. doi:10.1007/s00198-015-3164-4

SCB, Statistics Sweden (2013) http://www.scb.se (Accessed July 30 2013)

The National Board of Health and Welfare (2013) http://www.socialstyrelsen.se (Accessed July 30 2013)

FRAX®, WHO Fracture Risk Assessment Tool (2013) http://shef.ac.uk/FRAX/ (Accessed April 15 2013)

MPA (Läkemedelsverket) Läkemedelsboken (2011–2012) https://lakemedelsverket.se/upload/om-lakemedelsverket/publikationer/lakemedelsboken/LB2011-2012-interaktiv.pdf (Accessed 18 June 2015)

Adachi JD, Adami S, Gehlbach S, Anderson FA Jr, Boonen S, Chapurlat RD, Compston JE, Cooper C, Delmas P, Diez-Perez A et al (2010) Impact of prevalent fractures on quality of life: baseline results from the global longitudinal study of osteoporosis in women. Mayo Clin Proc 85:806–813

Silverman SL, Gold DT, Cramer JA (2007) Reduced fracture rates observed only in patients with proper persistence and compliance with bisphosphonate therapies. South Med J 100:1214–1218

Imaz I, Zegarra P, Gonzalez-Enriquez J, Rubio B, Alcazar R, Amate JM (2010) Poor bisphosphonate adherence for treatment of osteoporosis increases fracture risk: systematic review and meta-analysis. Osteoporos Int 21:1943–1951

Cramer JA, Gold DT, Silverman SL, Lewiecki EM (2007) A systematic review of persistence and compliance with bisphosphonates for osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int 18:1023–1031

Kothawala P, Badamgarav E, Ryu S, Miller RM, Halbert RJ (2007) Systematic review and meta-analysis of real-world adherence to drug therapy for osteoporosis. Mayo Clin Proc 82:1493–1501

Silverman SL (2010) Osteoporosis therapies: evidence from health-care databases and observational population studies. Calcif Tissue Int 87:375–384

Cramer JA, Silverman S, Gold DT (2007) Methodological considerations in using claims databases to evaluate persistence with bisphosphonates for osteoporosis. Curr Med Res Opin 23:2369–2377

(2009) Systematic Reviews: CRD’s guidance for undertaking reviews in health care. http://www.york.ac.uk/inst/crd/pdf/Systematic_Reviews.pdf (Accessed April 14 2014).

Brankin E, Walker M, Lynch N, Aspray T, Lis Y, Cowell W (2006) The impact of dosing frequency on compliance and persistence with bisphosphonates among postmenopausal women in the UK: evidence from three databases. Curr Med Res Opin 22:1249–1256

Burden AM, Paterson JM, Solomon DH, Mamdani M, Juurlink DN, Cadarette SM (2012) Bisphosphonate prescribing, persistence and cumulative exposure in Ontario, Canada. Osteoporos Int 23:1075–1082

Cheen MH, Kong MC, Zhang RF, Tee FM, Chandran M (2012) Adherence to osteoporosis medications amongst Singaporean patients. Osteoporos Int 23:1053–1060

Cotte FE, Fardellone P, Mercier F, Gaudin AF, Roux C (2010) Adherence to monthly and weekly oral bisphosphonates in women with osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int 21:145–155

Cotte FE, Mercier F, De Pouvourville G (2008) Relationship between compliance and persistence with osteoporosis medications and fracture risk in primary health care in France: a retrospective case–control analysis. Clin Ther 30:2410–2422

Cramer JA, Amonkar MM, Hebborn A, Altman R (2005) Compliance and persistence with bisphosphonate dosing regimens among women with postmenopausal osteoporosis. Curr Med Res Opin 21:1453–1460

Cramer JA, Lynch NO, Gaudin AF, Walker M, Cowell W (2006) The effect of dosing frequency on compliance and persistence with bisphosphonate therapy in postmenopausal women: a comparison of studies in the United States, the United Kingdom, and France. Clin Ther 28:1686–1694

Gold DT, Martin BC, Frytak JR, Amonkar MM, Cosman F (2007) A claims database analysis of persistence with alendronate therapy and fracture risk in post-menopausal women with osteoporosis. Curr Med Res Opin 23:585–594

Huybrechts KF, Ishak KJ, Caro JJ (2006) Assessment of compliance with osteoporosis treatment and its consequences in a managed care population. Bone 38:922–928

Jones TJ, Petrella RJ, Crilly R (2008) Determinants of persistence with weekly bisphosphonates in patients with osteoporosis. J Rheumatol 35:1865–1873

Li L, Roddam A, Gitlin M, Taylor A, Shepherd S, Shearer A, Jick S (2012) Persistence with osteoporosis medications among postmenopausal women in the UK General Practice Research Database. Menopause 19:33–40

Lo JC, Pressman AR, Omar MA, Ettinger B (2006) Persistence with weekly alendronate therapy among postmenopausal women. Osteoporos Int 17:922–928

McCombs JS, Thiebaud P, McLaughlin-Miley C, Shi J (2004) Compliance with drug therapies for the treatment and prevention of osteoporosis. Maturitas 48:271–287

Netelenbos JC, Geusens PP, Ypma G, Buijs SJ (2011) Adherence and profile of non-persistence in patients treated for osteoporosis—a large-scale, long-term retrospective study in The Netherlands. Osteoporos Int 22:1537–1546

Penning-van Beest FJ, Goettsch WG, Erkens JA, Herings RM (2006) Determinants of persistence with bisphosphonates: a study in women with postmenopausal osteoporosis. Clin Ther 28:236–242

Rabenda V, Mertens R, Fabri V, Vanoverloop J, Sumkay F, Vannecke C, Deswaef A, Verpooten GA, Reginster JY (2008) Adherence to bisphosphonates therapy and hip fracture risk in osteoporotic women. Osteoporos Int 19:811–818

Solomon DH, Avorn J, Katz JN, Finkelstein JS, Arnold M, Polinski JM, Brookhart MA (2005) Compliance with osteoporosis medications. Arch Intern Med 165:2414–2419

Ström O, Landfeldt E (2012) The association between automatic generic substitution and treatment persistence with oral bisphosphonates. Osteoporos Int 23:2201–2209

van den Boogaard CH, Breekveldt-Postma NS, Borggreve SE, Goettsch WG, Herings RM (2006) Persistent bisphosphonate use and the risk of osteoporotic fractures in clinical practice: a database analysis study. Curr Med Res Opin 22:1757–1764

Vanelli M, Pedan A, Liu N, Hoar J, Messier D, Kiarsis K (2009) The role of patient inexperience in medication discontinuation: a retrospective analysis of medication nonpersistence in seven chronic illnesses. Clin Ther 31:2628–2652

Weycker D, Macarios D, Edelsberg J, Oster G (2006) Compliance with drug therapy for postmenopausal osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int 17:1645–1652

Yeaw J, Benner JS, Walt JG, Sian S, Smith DB (2009) Comparing adherence and persistence across 6 chronic medication classes. J Manag Care Pharm 15:728–740

Yu SF, Chou CL, Lai HM, Chen YC, Chiu CK, Kuo MC, Su YJ, Chen CJ, Cheng TT (2012) Adherence to anti-osteoporotic regimens in a Southern Taiwanese population treated according to guidelines: a hospital-based study. Int J Rheum Dis 15:297–305

Gallagher AM, Rietbrock S, Olson M, van Staa TP (2008) Fracture outcomes related to persistence and compliance with oral bisphosphonates. J Bone Miner Res 23:1569–1575

Gold DT, Trinh H, Safi W (2009) Weekly versus monthly drug regimens: 1-year compliance and persistence with bisphosphonate therapy. Curr Med Res Opin 25:1831–1839

Hadji P, Claus V, Ziller V, Intorcia M, Kostev K, Steinle T (2012) GRAND: the German retrospective cohort analysis on compliance and persistence and the associated risk of fractures in osteoporotic women treated with oral bisphosphonates. Osteoporos Int 23:223–231

Weiss TW, Henderson SC, McHorney CA, Cramer JA (2007) Persistence across weekly and monthly bisphosphonates: analysis of US retail pharmacy prescription refills. Curr Med Res Opin 23:2193–2203

Hansen C, Pedersen BD, Konradsen H, Abrahamsen B (2013) Anti-osteoporotic therapy in Denmark—predictors and demographics of poor refill compliance and poor persistence. Osteoporos Int 24:2079–2097

Cheng TT, Yu SF, Hsu CY, Chen SH, Su BY, Yang TS (2013) Differences in adherence to osteoporosis regimens: a 2-year analysis of a population treated under specific guidelines. Clin Ther 35:1005–1015

Curtis JR, Westfall AO, Allison JJ, Freeman A, Saag KG (2006) Channeling and adherence with alendronate and risedronate among chronic glucocorticoid users. Osteoporos Int 17:1268–1274

McGowan B, Bennett K, Casey MC, Doherty J, Silke C, Whelan B (2013) Comparison of prescribing and adherence patterns of anti-osteoporotic medications post-admission for fragility type fracture in an urban teaching hospital and a rural teaching hospital in Ireland between 2005 and 2008. Ir J Med Sci 182:601–608

van Boven JF, de Boer PT, Postma MJ, Vegter S (2013) Persistence with osteoporosis medication among newly-treated osteoporotic patients. J Bone Miner Metab 31:562–570

Ziller V, Kostev K, Kyvernitakis I, Boeckhoff J, Hadji P (2012) Persistence and compliance of medications used in the treatment of osteoporosis—analysis using a large scale, representative, longitudinal German database. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther 50:315–322

Wade SW, Curtis JR, Yu J, White J, Stolshek BS, Merinar C, Balasubramanian A, Kallich JD, Adams JL, Viswanathan HN (2012) Medication adherence and fracture risk among patients on bisphosphonate therapy in a large United States health plan. Bone 50:870–875

Balasubramanian A, Brookhart MA, Goli V, Critchlow CW (2013) Discontinuation and reinitiation patterns of osteoporosis treatment among commercially insured postmenopausal women. Int J Gen Med 6:839–848

Chiu CK, Kuo MC, Yu SF, Su BY, Cheng TT (2013) Adherence to osteoporosis regimens among men and analysis of risk factors of poor compliance: a 2-year analytical review. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 14:276

Xu Y, Viswanathan HN, Ward MA, Clay B, Adams JL, Stolshek BS, Kallich JD, Fine S, Saag KG (2013) Patterns of osteoporosis treatment change and treatment discontinuation among commercial and medicare advantage prescription drug members in a national health plan. J Eval Clin Pract 19:50–59

Sheehy O, Kindundu C, Barbeau M, LeLorier J (2009) Adherence to weekly oral bisphosphonate therapy: cost of wasted drugs and fractures. Osteoporos Int 20:1583–1594

Silverman SL, Gold DT (2008) Compliance and persistence with osteoporosis therapies. Curr Rheumatol Rep 10:118–122

de Groen PC, Lubbe DF, Hirsch LJ, Daifotis A, Stephenson W, Freedholm D, Pryor-Tillotson S, Seleznick MJ, Pinkas H, Wang KK (1996) Esophagitis associated with the use of alendronate. N Engl J Med 335:1016–1021

Acknowledgments

Editing support was provided by Claire Desborough, Amgen (Europe) GmbH, and Oxford PharmaGenesis Ltd, Oxford, UK (funded by Amgen). The authors also thank Fereshte Ebrahim, National Board of Health and Welfare, Sweden, for sample extraction. The study was sponsored by Amgen Inc.

Conflicts of interest

LK and OS have previously consulted for companies marketing products for osteoporosis. JL, EP, and MI are employed by Amgen Inc.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Karlsson, L., Lundkvist, J., Psachoulia, E. et al. Persistence with denosumab and persistence with oral bisphosphonates for the treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis: a retrospective, observational study, and a meta-analysis. Osteoporos Int 26, 2401–2411 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-015-3253-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-015-3253-4