Abstract

Summary

Limited information is available on anti-osteoporotic treatment initiation patterns in France. In 2006–2013, the most frequently prescribed first-line treatment class for osteoporosis was represented by bisphosphonates (alendronic acid and risedronic acid), followed by strontium ranelate. Persistence with anti-osteoporotic treatment was low, with high proportions of treatment discontinuations and switches.

Introduction

This epidemiological, longitudinal study described first-line treatment initiation, persistence, switches to second-line treatment, and medical care consumption in osteoporotic patients in France during the 2007–2013 period.

Methods

Patients aged ≥50 years, who were recorded in a French claims database and did not die during the observation period, were included if they met ≥1 inclusion criteria for osteoporosis in 2007 (≥1 reimbursement for anti-osteoporotic treatment, hospitalisation for osteoporotic fracture (spine, hip, femur, forearm bones, humerus, wrist), or ≥1 reimbursement for long-term osteoporosis-associated status). We collected data on consumption of anti-osteoporotic treatment (alendronic acid, ibandronic acid, risedronic acid, zoledronic acid, raloxifene, strontium ranelate, teriparatide) and of osteoporosis-related medical care after the date of first reimbursement for anti-osteoporotic treatment.

Results

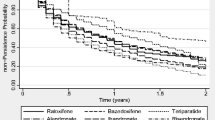

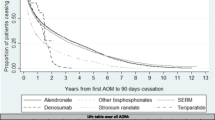

We obtained 2219 patients with a 6-year follow-up and 1387 who initiated an anti-osteoporotic treatment in 2007 and who can be selected for the treatment regimen analysis. The most frequently used first-line treatments were alendronic acid (32.7 %), risedronic acid (22.4 %), strontium ranelate (19.3 %), ibandronic acid (13.1 %) and raloxifene (12.2 %). Among patients who received these treatments, the highest persistence after 6 years was observed for raloxifene (37.3 %), alendronic acid (35.1 %) and risedronic acid (32.3 %). Treatment discontinuations were reported for 35.5 % (raloxifene) to 53.4 % (strontium ranelate) and treatment switches for 27.4 % (alendronic acid) to 56.6 % (ibandronic acid) of these patients.

Conclusions

This study showed that persistence with anti-osteoporotic treatment was relatively low in France, with high proportions of treatment discontinuations and switches, and that patients with osteoporosis were insufficiently monitored by bone specialists.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Kanis JA (1994) Assessment of fracture risk and its application to screening for postmenopausal osteoporosis: synopsis of a WHO report. WHO study group. Osteoporos Int 4:368–381

Bliuc D, Nguyen ND, Milch VE, Nguyen TV, Eisman JA, Center JR (2009) Mortality risk associated with low-trauma osteoporotic fracture and subsequent fracture in men and women. JAMA 301:513–521. doi:10.1001/jama.2009.50

Briot K, Cortet B, Thomas T, Audran M, Blain H, Breuil V, Chapuis L, Chapurlat R, Fardellone P, Feron JM, Gauvain JB, Guggenbuhl P, Kolta S, Lespessailles E, Letombe B, Marcelli C, Orcel P, Seret P, Tremollieres F, Roux C (2012) 2012 update of French guidelines for the pharmacological treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis. Joint Bone Spine 79:304–313. doi:10.1016/j.jbspin.2012.02.014

Ström O, Borgström F, Kanis J, Compston J, Cooper C, McCloskey E, Jönsson B (2011) Osteoporosis: burden, health care provision and opportunities in the EU. Arch Osteoporos 6:59–155. doi:10.1007/s11657-011-0060-1

Lespessailles E, Cotte FE, Roux C, Fardellone P, Mercier F, Gaudin AF (2009) Prevalence and features of osteoporosis in the French general population: the instant study. Joint Bone Spine 76:394–400. doi:10.1016/j.jbspin.2008.10.008

Kanis JA on behalf of the World Health Organisation Scientific Group (2007). Assessment of osteoporosis at the primary health care level. Technical Report. World Health Organisation Collaborating Center for Metabolic Bone diseases, University of Sheffield, UK. Printed by the University of Sheffield. http://www.shef.ac.uk/FRAX/pdfs/WHO_Technical_Report.pdf. Accessed 8 April 2016.

Siris ES, Miller PD, Barrett-Connor E, Faulkner KG, Wehren LE, Abbott TA, Berger ML, Santora AC, Sherwood LM (2001) Identification and fracture outcomes of undiagnosed low bone mineral density in postmenopausal women: results from the National Osteoporosis Risk Assessment. JAMA 286:2815–2822

Unnanuntana A, Gladnick BP, Donnelly E, Lane JM (2010) The assessment of fracture risk. J Bone Joint Surg Am 92:743–753. doi:10.2106/JBJS.I.00919

Agence Française de Sécurité Sanitaire des Produits de Santé (2006). Traitement medicamenteux de l’ostéoporose post-ménopausique—recommandations—actualisation 2006. http://www.grio.org/documents/rcd-4-1263309820.pdf. Accessed 8 April 2016.

Kanis JA, Johnell O, Oden A, Johansson H, McCloskey E (2008) FRAX and the assessment of fracture probability in men and women from the UK. Osteoporos Int 19:385–397. doi:10.1007/s00198-007-0543-5

Feurer E, Chapurlat R (2014) Emerging drugs for osteoporosis. Expert Opin Emerg Drugs 19:385–395. doi:10.1517/14728214.2014.936377

Kanis JA, McCloskey EV, Johansson H, Cooper C, Rizzoli R, Reginster JY, Scientific Advisory Board of the European Society for C, Economic Aspects of O, Osteoarthritis, the Committee of Scientific Advisors of the International Osteoporosis F (2013) European guidance for the diagnosis and management of osteoporosis in postmenopausal women. Osteoporos Int 24:23–57. doi:10.1007/s00198-012-2074-y

Hermann AP, Abrahamsen B (2013) The bisphosphonates: risks and benefits of long term use. Curr Opin Pharmacol 13:435–439. doi:10.1016/j.coph.2013.02.002

Kostoff MD, Saseen JJ, Borgelt LM (2014) Evaluation of fracture risk and potential drug holidays for postmenopausal women on long-term bisphosphonate therapy. Int J Womens Health 6:423–428. doi:10.2147/IJWH.S57549

McClung M, Harris ST, Miller PD, Bauer DC, Davison KS, Dian L, Hanley DA, Kendler DL, Yuen CK, Lewiecki EM (2013) Bisphosphonate therapy for osteoporosis: benefits, risks, and drug holiday. Am J Med 126:13–20. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2012.06.023

Bone HG, Chapurlat R, Brandi ML, Brown JP, Czerwinski E, Krieg MA, Mellstrom D, Radominski SC, Reginster JY, Resch H, Ivorra JA, Roux C, Vittinghoff E, Daizadeh NS, Wang A, Bradley MN, Franchimont N, Geller ML, Wagman RB, Cummings SR, Papapoulos S (2013) The effect of three or six years of denosumab exposure in women with postmenopausal osteoporosis: results from the FREEDOM extension. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 98:4483–4492. doi:10.1210/jc.2013-1597

Caisse nationale de l’Assurance Maladie des travailleurs salariés (2015). Améliorer la qualité du système de santé et maîtriser les dépenses. Propositions de l’Assurance Maladie pour 2016. http://www.ameli.fr/rapport-charges-et-produits-2016/#/0. Accessed 20 May 2016.

Cosman F, de Beur SJ, LeBoff MS, Lewiecki EM, Tanner B, Randall S, Lindsay R (2014) Clinician’s guide to prevention and treatment of osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int 25:2359–2381. doi:10.1007/s00198-014-2794-2

Dargent-Molina P (2004) Epidemiology and risk factors for osteoporosis. Rev Med Interne 25(Suppl 5):S517–S525

De Roquefeuil L, Studer A, Neumann A, Merlière Y (2009) The Echantillon généraliste de bénéficiaires: representativeness, scope and limits. Prat Organ. Soins 40:213–223

Direction de la stratégie des études et des statistiques de la Caisse Nationale d’Assurance Maladie des Travailleurs Salariés (CNAMTS). Generalist Sample of Beneficiaries (EGB)—SNIIR-AM (National Health Insurance Cross-Schemes Information System). https://epidemiologie-france.aviesan.fr/en/epidemiology/records/echantillon-generaliste-de-beneficiaires-sniir-am. Accessed 8 April 2016.

Haute Autorité de la Santé. Transparency Committee Opinion. 19 December 2007. ACLASTA: inclusion on the list of medicines reimbursed by National Insurance and approved for use by hospitals in the extension of indication: “Treatment of osteoporosis in postmenopausal women at high risk of fracture.” Available from: http://www.has-sante.fr/portail/upload/docs/application/pdf/2010-11/aclasta_ct_5082.pdf. Accessed on 6 May 2016.

Pernicova I, Middleton ET, Aye M (2008) Rash, strontium ranelate and DRESS syndrome put into perspective. European medicine agency on the alert. Osteoporos Int 19:1811–1812. doi:10.1007/s00198-008-0734-8

Confavreux CB, Canoui-Poitrine F, Schott AM, Ambrosi V, Tainturier V, Chapurlat RD (2012) Persistence at 1 year of oral antiosteoporotic drugs: a prospective study in a comprehensive health insurance database. Eur J Endocrinol 166:735–741. doi:10.1530/EJE-11-0959

Modi A, Sajjan S, Gandhi S (2014) Challenges in implementing and maintaining osteoporosis therapy. Int J Womens Health 6:759–769. doi:10.2147/IJWH.S53489

Cotte FE, Mercier F, De Pouvourville G (2008b) Relationship between compliance and persistence with osteoporosis medications and fracture risk in primary health care in France: a retrospective case-control analysis. Clin Ther 30:2410–2422. doi:10.1016/j.clinthera.2008.12.019

Cotte FE, Cortet B, Lafuma A, Avouac B, Hasnaoui AE, Fardellone P, Pouchain D, Roux C, Gaudin AF (2008a) A model of the public health impact of improved treatment persistence in post-menopausal osteoporosis in France. Joint Bone Spine 75:201–208. doi:10.1016/j.jbspin.2007.06.004

Nikitovic M, Solomon DH, Cadarette SM (2010) Methods to examine the impact of compliance to osteoporosis pharmacotherapy on fracture risk: systematic review and recommendations. Ther Adv Chronic Dis 1:149–162. doi:10.1177/2040622310376137

Yun H, Curtis JR, Guo L, Kilgore M, Muntner P, Saag K, Matthews R, Morrisey M, Wright NC, Becker DJ, Delzell E (2014) Patterns and predictors of osteoporosis medication discontinuation and switching among Medicare beneficiaries. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 15:112. doi:10.1186/1471-2474-15-112

Cotte FE, De Pouvourville G (2011) Cost of non-persistence with oral bisphosphonates in post-menopausal osteoporosis treatment in France. BMC Health Serv Res 11:151. doi:10.1186/1472-6963-11-151

Halpern R, Becker L, Iqbal SU, Kazis LE, Macarios D, Badamgarav E (2011) The association of adherence to osteoporosis therapies with fracture, all-cause medical costs, and all-cause hospitalizations: a retrospective claims analysis of female health plan enrollees with osteoporosis. J Manag Care Pharm 17:25–39

Modi A, Siris ES, Tang J, Sen S (2015) Cost and consequences of noncompliance with osteoporosis treatment among women initiating therapy. Curr Med Res Opin 31:757–765. doi:10.1185/03007995.2015.1016605

Karlsson L, Lundkvist J, Psachoulia E, Intorcia M, Ström O (2015) Persistence with denosumab and persistence with oral bisphosphonates for the treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis: a retrospective, observational study, and a meta-analysis. Osteoporos Int 26(10):2401–2411. doi:10.1007/s00198-015-3253-4

Landfeldt E, Ström O, Robbins S, Borgstrom F (2012) Adherence to treatment of primary osteoporosis and its association to fractures—the Swedish adherence register analysis (SARA). Osteoporos Int 23:433–443. doi:10.1007/s00198-011-1549-6

Ström O, Landfeldt E (2012) The association between automatic generic substitution and treatment persistence with oral bisphosphonates. Osteoporos Int 23:2201–2209. doi:10.1007/s00198-011-1850-4

Penning-van Beest FJ, Erkens JA, Olson M, Herings RM (2008) Determinants of non-compliance with bisphosphonates in women with postmenopausal osteoporosis. Curr Med Res Opin 24:1337–1344. doi:10.1185/030079908X297358

Erny F, Auvinet A, Chu Miow Lin D, Pioger A, Haguenoer K, Tauveron P, Jacquot F, Rusch E, Goupille P, Mulleman D (2015) Management of osteoporosis in women after forearm fracture: data from a French health insurance database. Joint Bone Spine 82:52–55. doi:10.1016/j.jbspin.2014.07.007

Haute Autorité de Santé (2011). PROLIA: Inscription Sécurité Sociale et Collectivités http://www.has-sante.fr/portail/upload/docs/application/pdf/2012-03/prolia_14122011_avis_ct10890.pdf. Accessed 8 April 2016.

Gosselin J, Bougnères C, Bennet P, Avenel G, Vittecoq O, Daragon A (2016) Impact des nouvelles recommandations du traitement médicamenteux de l’ostéoporose post-ménopausique. Étude rétrospective des patientes vues en consultation « ostéoporose » entre 2006 et 2012. Rev Rhum. doi:10.1016/j.rhum.2015.01.001

Acknowledgments

We thank the French National Health Service (Caisse Nationale de l’Assurance Maladie des Travailleurs Salariés) and the Institute of Health Data (Institut des Données de Santé) for providing data. The authors thank Claire Verbelen (XPE Pharma and Science, Wavre, Belgium) for professional medical writing support. This study was funded by MSD France.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

MB was a PhD student and part-time employee of MSD France at the time of the study. CBC received honorarium from Amgen, Lilly, MSD. BC received honorarium from Amgen, Ferring, Lilly, Medtronic, MSD, Roche diagnostics. LL is a full-time employee of MSD France. MG has nothing to declare. EVG has nothing to declare.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Belhassen, M., Confavreux, C.B., Cortet, B. et al. Anti-osteoporotic treatments in France: initiation, persistence and switches over 6 years of follow-up. Osteoporos Int 28, 853–862 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-016-3789-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-016-3789-y