Abstract

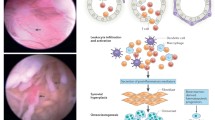

Synovial immunopathology in rheumatoid arthritis is complex involving both resident and infiltrating cells. The synovial tissue undergoes significant neovascularization, facilitating an influx of lymphocytes and monocytes that transform a typically acellular loose areolar membrane into an invasive tumour-like pannus. The microvasculature proliferates to form straight regularly-branching vessels; however, they are highly dysfunctional resulting in reduced oxygen supply and a hypoxic microenvironment. Autoantibodies such as rheumatoid factor and anti-citrullinated protein antibodies are found at an early stage, often before arthritis has developed, and they have been implicated in the pathogenesis of RA. Abnormal cellular metabolism and mitochondrial dysfunction thus ensue and, in turn, through the increased production of reactive oxygen species actively induce inflammation. Key pro-inflammatory cytokines, chemokines and growth factors and their signalling pathways, including nuclear factor κB, Janus kinase-signal transducer, are highly activated when immune cells are exposed to hypoxia in the inflamed rheumatoid joint show adaptive survival reactions by activating. This review attempts to highlight those aberrations in the innate and adaptive immune systems including the role of genetic and environmental factors, autoantibodies, cellular alterations, signalling pathways and metabolism that are implicated in the pathogenesis of RA and may therefore provide an opportunity for therapeutic intervention.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

McInnes IB, Schett G (2007) Cytokines in the pathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis. Nat Rev Immunol 7:429–442

van der Heijde DM (1995) Joint erosions and patients with early rheumatoid arthritis. Br J Rheumatol 34:74–78

Orr C et al (2017) Synovial immunophenotype and anti-citrullinated protein antibodies in rheumatoid arthritis patients: relationship to treatment response and radiological prognosis. Ann Rheum Dis

Gerlag DM et al (2012) EULAR recommendations for terminology and research in individuals at risk of rheumatoid arthritis: report from the study group for risk factors for rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 71:638–641

van de Sande MG et al (2011) Different stages of rheumatoid arthritis: features of the synovium in the preclinical phase. Ann Rheum Dis 70:772–777

Nielen MMJ et al (2004) Specific autoantibodies precede the symptoms of rheumatoid arthritis: a study of serial measurements in blood donors. Arthritis Rheum 50:380–386. doi:10.1002/art.20018

Rantapaa-Dahlqvist S et al (2003) Antibodies against cyclic citrullinated peptide and IgA rheumatoid factor predict the development of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 48:2741–2749

de Hair MJ et al (2014) Features of the synovium of individuals at risk of developing rheumatoid arthritis: implications for understanding preclinical rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol 66:513–522. doi:10.1002/art.38273

Bos WH et al (2010) Arthritis development in patients with arthralgia is strongly associated with anti-citrullinated protein antibody status: a prospective cohort study. Ann Rheum Dis 69:490–494

van der Heide A et al (1996) The effectiveness of early treatment with “second-line” antirheumatic drugs. A randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med 124:699–707

Lard LR et al (2001) Early versus delayed treatment in patients with recent-onset rheumatoid arthritis: comparison of two cohorts who received different treatment strategies. Am J Med 111:446–451

Nell VPK et al (2004) Benefit of very early referral and very early therapy with disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs in patients with early rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology 43:906–914

Smolen JS et al (2010) EULAR recommendations for the management of rheumatoid arthritis with synthetic and biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs. Ann Rheumatic Dis 69:964–975

Baeten D et al (2000) Comparative study of the synovial histology in rheumatoid arthritis, spondyloarthropathy, and osteoarthritis: influence of disease duration and activity. Ann Rheum Dis 59:945–953

Tak PP et al (1995) Expression of adhesion molecules in early rheumatoid synovial tissue. Clin Immunol Immunopathol 77:236–242

Smeets TJ et al (1998) Poor expression of T cell-derived cytokines and activation and proliferation markers in early rheumatoid synovial tissue. Clin Immunol Immunopathol 88:84–90

Yeo L et al (2016) Expression of chemokines CXCL4 and CXCL7 by synovial macrophages defines an early stage of rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 75:763–771

Klarenbeek PL et al (2012) Inflamed target tissue provides a specific niche for highly expanded T-cell clones in early human autoimmune disease. Ann Rheum Dis 71:1088–1093

Raza K et al (2005) Early rheumatoid arthritis is characterized by a distinct and transient synovial fluid cytokine profile of T cell and stromal cell origin. Arthritis Res Ther 7:R784–R795

Hurd ER (1979) Extraarticular manifestations of rheumatoid arthritis. Semin Arthritis Rheum 8:151–176

Cimmino MA et al (2000) Extra-articular manifestations in 587 Italian patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatol Int 19:213–217

Sugiyama D et al (2010) Impact of smoking as a risk factor for developing rheumatoid arthritis: a meta-analysis of observational studies. Ann Rheum Dis 69:70–81

Stolt P et al (2003) Quantification of the influence of cigarette smoking on rheumatoid arthritis: results from a population based case-control study, using incident cases. Ann Rheum Dis 62:835–841

Di Giuseppe D et al (2014) Cigarette smoking and risk of rheumatoid arthritis: a dose-response meta-analysis. Arthritis Res Ther 16:R61

Padyukov L et al (2004) A gene-environment interaction between smoking and shared epitope genes in HLA-DR provides a high risk of seropositive rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 50:3085–3092

Klareskog L et al (2006) Mechanisms of disease: genetic susceptibility and environmental triggers in the development of rheumatoid arthritis. Nat Clin Pract Rheumatol 2:425–433

Lu B et al (2014) Associations of smoking and alcohol consumption with disease activity and functional status in rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol 41:24–30

Saag KG et al (1997) Cigarette smoking and rheumatoid arthritis severity. Ann Rheum Dis 56:463–469

Masdottir B et al (2000) Smoking, rheumatoid factor isotypes and severity of rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 39:1202–1205

Tedeschi SK, Costenbader KH (2016) Is there a role for diet in the therapy of rheumatoid arthritis? Curr Rheumatol Rep 18:23

Naranjo A et al (2008) Cardiovascular disease in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: results from the QUEST-RA study. Arthritis Res Ther 10:R30

Armstrong DJ et al (2006) Obesity and cardiovascular risk factors in rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 45:782

Maxwell JR et al (2010) Alcohol consumption is inversely associated with risk and severity of rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 49:2140–2146

Källberg H et al (2009) Alcohol consumption is associated with decreased risk of rheumatoid arthritis: results from two Scandinavian case-control studies. Ann Rheumatic Dis 68:222–227

Scott IC et al (2013) The protective effect of alcohol on developing rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 52:856–867

Jonsson IM et al (2007) Ethanol prevents development of destructive arthritis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 104:258–263

Krco CJ et al (1996) Characterization of the antigenic structure of human type II collagen. J Immunol 156:2761–2768

Auger I, Roudier J (1997) A function for the QKRAA amino acid motif: mediating binding of DnaJ to DnaK. Implications for the association of rheumatoid arthritis with HLA-DR4. J Clin Invest 99:1818–1822

Wegner N et al (2010) Peptidylarginine deiminase from Porphyromonas gingivalis citrullinates human fibrinogen and alpha-enolase: implications for autoimmunity in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 62:2662–2672

Kouri T et al (1990) Antibodies to synthetic peptides from Epstein-Barr nuclear antigen-1 in sera of patients with early rheumatoid arthritis and in preillness sera. J Rheumatol 17:1442–1449

Blaschke S et al (2000) Epstein-Barr virus infection in peripheral blood mononuclear cells, synovial fluid cells, and synovial membranes of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol 27:866–873

Ebringer A et al (1985) Antibodies to proteus in rheumatoid arthritis. Lancet 2:305–307

Ray NB et al (2001) Induction of an invasive phenotype by human parvovirus B19 in normal human synovial fibroblasts. Arthritis Rheum 44:1582–1586

Kanagawa H et al (2015) Mycobacterium tuberculosis promotes arthritis development through Toll-like receptor 2. J Bone Miner Metab 33:135–141

Forslind K et al (2007) Sex: a major predictor of remission in early rheumatoid arthritis? Ann Rheum Dis 66:46–52

Cutolo M et al (2000) The hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortical and gonadal axis function in rheumatoid arthritis. Z Rheumatol 59:II/65–II/69

Cutolo M et al (2006) Estrogens and autoimmune diseases. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1089:538–547

Gordon D et al (1988) Prolonged hypogonadism in male patients with rheumatoid arthritis during flares in disease activity. Br J Rheumatol 27:440–444

Auci D et al (2007) A new orally bioavailable syntheic androstene inhibits collagen-induced arthritis in the mouse. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1110:630–640

Röntzsch A et al (2004) Amelioration of murine antigen-induced arthritis by dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA). Inflamm Research 53:189–198

Hassfeld W et al (1989) Demonstration of a new antinuclear antibody (anti-RA33) that is highly specific for rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 32:1515–1520

Skriner K et al (1997) Anti-A2 / RA33 autoantibodies are directed to the RNA binding region of the A2 protein of the heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein complex. J Clin Invest 100:127–135

Shi J et al (2011) Autoantibodies recognizing carbamylated proteins are present in sera of patients with rheumatoid arthritis and predict joint damage. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA 108:17372–17377

Schellekens GA et al (2000) The diagnostic properties of rheumatoid arthritis antibodies recognizing a cyclic citrullinated peptide. Arthritis Rheum 43:155–163

Rantapää-Dahlqvist S et al (2003) Antibodies against cyclic citrullinated peptide and IgA rheumatoid factor predict the development of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 48:2741–2749

Mjaavatten MD et al (2009) Positive anti-citrullinated protein antibody status and small joint arthritis are consistent predictors of chronic disease in patients with very early arthritis: results from the NOR-VEAC cohort. Arthritis Res Ther 11:R146. doi:10.1186/ar2820. 63

Machold KP et al (2007) Very recent onset rheumatoid arthritis: clinical and serological patient characteristics associated with radiographic progression over the first years of disease. Rheumatology (Oxford) 46:342–349

van der Helm-van Mil AH et al (2005) Antibodies to citrullinated proteins and differences in clinical progression of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Res Ther 7:R949–R958

Jansen LM et al (2003) The predictive value of anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide antibodies in early arthritis. J Rheumatol 30:1691–1695

Kroot EJ et al (2000) The prognostic value of anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide antibody in patients with recent-onset rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 43:1831–1835

Syversen SW et al (2008) High anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide levels and an algorithm of four variables predict radiographic progression in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: results from a 10-year longitudinal study. Ann Rheum Dis 67:212–217

Aubart F et al (2011) High levels of anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide autoantibodies are associated with co-occurrence of pulmonary diseases with rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol 38:979–982

Nordberg LB et al (2017) Patients with seronegative RA have more inflammatory activity compared with patients with seropositive RA in an inception cohort of DMARD-naive patients classified according to the 2010 ACR/EULAR criteria. Ann Rheum Dis 76:341–345

Waaler E (2007) On the occurrence of a factor in human serum activating the specific agglutintion of sheep blood corpuscles. 1939. APMIS : acta pathologica, microbiologica, et immunologica Scandinavica 115:422–438

Masi AT (1976) Prospective study of the early course of rheumatoid arthritis in young adults:comparison of patients with and without rheumatoid factor positivity at entry and identification of variables correlating with outcome. Semin Arthritis Rheum 4:299–326

Shiel WC Jr, Jason M (1989) The diagnostic associations of patients with antinuclear antibodies referred to a community rheumatologist. J Rheumatol 16:782–785

Slater CA et al (1996) Antinuclear antibody testing. A study of clinical utility. Arch Intern Med 156:1421–1425

Smith MD et al (2003) Microarchitecture and protective mechanisms in synovial tissue from clinically and arthroscopically normal knee joints. Ann Rheum Dis 62:303–307

Firestein GS, Veale DJ (2016) Synovium. In: Kelley and Firestein’s (ed) Textbook of rheumatology, 10th edn. Elsevier Health Sciences

Rhee DK et al (2005) The secreted glycoprotein lubricin protects cartilage surfaces and inhibits synovial cell overgrowth. J Clin Invest 115:622–631

Hyc A et al (2009) Pro-and anti-inflammatory cytokines increase hyaluronan production by rat synovial membrane in vitro. Int J Mol Med 24(4):579

Blewis ME et al (2009) Interactive cytokine regulation of synoviocyte lubricant secretion. Tissue Eng Part A 16:1329–1337

Cretu D et al (2013) Delineating the synovial fluid proteome: recent advancements and ongoing challenges in biomarker research. Crit Rev Clin Lab Sci 50:51–63

Oliver KM et al (2009) Hypoxia activates NF-kappaB-dependent gene expression through the canonical signaling pathway. Antioxid Redox Signal 11:2057–2064

Gao W et al (2015) Hypoxia and STAT3 signalling interactions regulate pro-inflammatory pathways in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 74:1275–1283

Tchetverikov I et al (2005) MMP protein and activity levels in synovial fluid from patients with joint injury, inflammatory arthritis, and osteoarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 64:694–698

Fearon U et al (1999) Synovial cytokine and growth factor regulation of MMPs/TIMPs: implications for erosions and angiogenesis in early rheumatoid and psoriatic arthritis patients. Ann N Y Acad Sci 30:619–621

Tak PP et al (1997) Analysis of the synovial cell infiltrate in early rheumatoid synovial tissue in relation to local disease activity. Arthritis Rheum 40:217–225

Smith MD et al (2006) Standardisation of synovial tissue infiltrate analysis: how far have we come? How much further do we need to go? Ann Rheum Dis 65:93–100

Kennedy A et al (2010) Angiogenesis and blood vessel stability in inflammatory arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 62:711–721

Epstein FH, Harris ED Jr (1990) Rheumatoid arthritis: pathophysiology and implications for therapy. New Eng J Med 322:1277–1289

Månsson B et al (1995) Cartilage and bone metabolism in rheumatoid arthritis. Differences between rapid and slow progression of disease identified by serum markers of cartilage metabolism. J Clin Invest 95:1071–1077

Ng CT et al (2010) Synovial tissue hypoxia and inflammation in vivo. Ann Rheum Dis 69:1389–1395

Fearon U et al (2003) Angiopoietins, growth factors, and vascular morphology in early arthritis. J Rheumatol 30:260–268

Fraser A et al (2001) Matrix metalloproteinase 9, apoptosis, and vascular morphology in early arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 44:2024–2028

García S et al (2014) Tie2 signaling cooperates with TNF to promote the pro-inflammatory activation of human macrophages independently of macrophage functional phenotype. PLoS One 9(1):e82088. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0082088

Krausz S et al (2012) Angiopoietin-2 promotes inflammatory activation of human macrophages. Ann Rheum Dis 71:1402–1410

Fearon U et al (2016) Hypoxia, mitochondrial dysfunction and synovial invasiveness in rheumatoid arthritis. Nat Rev Rheumatol 12:385–397

Levick JR (1981) Permeability of rheumatoid and normal human synovium to specific plasma proteins. Arthritis Rheum 24:1550–1560

Dahl LB et al (1985) Concentration and molecular weight of sodium hyaluronate in synovial fluid from patients with rheumatoid arthritis and other arthropathies. Ann Rheum Dis 44:817–822

Hui AY et al (2012) A systems biology approach to synovial joint lubrication in health, injury, and disease. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Syst Biol Med 4:15–37

Reece RJ et al (1999) Distinct vascular patterns of early synovitis in psoriatic, reactive, and rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis & Rheumatism 42(7):1481–1484

Izquierdo E et al (2009) Immature blood vessels in rheumatoid synovium are selectively depleted in response to anti-TNF therapy. PLoS One 4(12):e8131. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0008131

Dennis G Jr et al (2014) Synovial phenotypes in rheumatoid arthritis correlate with response to biologic therapeutics. Arthritis Res Ther 16(2):R90

Mulherin D et al (1996) Synovial tissue macrophage populations and articular damage in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 39:115–124

Smolen JS, Steiner G (2003) Therapeutic strategies for rheumatoid arthritis. Nat Rev Drug Dis 2:473–488

Haringman JJ et al (2005) Synovial tissue macrophages: a sensitive biomarker for response to treatment in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 64:834–838

Bresnihan B et al (2009) Synovial tissue sublining CD68 expression is a biomarker of therapeutic response in rheumatoid arthritis clinical trials: consistency across centers. J Rheumatol 36:1800–1802

Szekanecz Z, Koch AE (2007) Macrophages and their products in rheumatoid arthritis. Curr Opin Rheumatol 19:289–295

McInnes IB et al (2000) Cell-cell interactions in synovitis. Interactions between T lymphocytes and synovial cells. Arthritis Res 2:374–378

Burger D, Dayer J-M (2002) The role of human T-lymphocyte-monocyte contact in inflammation and tissue destruction. Arthritis Res 4(Suppl 3):S169–S176

Soler Palacios B et al (2015) Macrophages from the synovium of active rheumatoid arthritis exhibit an activin A-dependent pro-inflammatory profile. J Pathol 235:515–526

Strehl C et al (2014) Hypoxia: how does the monocyte-macrophage system respond to changes in oxygen availability? J Leukoc Biol 95:233–241. doi:10.1189/jlb.1212627

Iguchi T, Ziff M (1986) Electron microscopic study of rheumatoid synovial vasculature. Intimate relationship between tall endothelium and lymphoid aggregation. J Clin Invest 77:355–361

Cañete JD et al (2009) Clinical significance of synovial lymphoid neogenesis and its reversal after anti-tumour necrosis factor alpha therapy in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 68:751–756

Klimiuk PA et al (2003) Circulating tumour necrosis factor alpha and soluble tumour necrosis factor receptors in patients with different patterns of rheumatoid synovitis. Ann Rheum Dis 62:472–475

Miossec P et al (2009) Interleukin-17 and type 17 helper T cells. N Engl J Med 361:888–898

Lubberts E et al (2005) The role of T-cell interleukin-17 in conducting destructive arthritis: lessons from animal models. Arthritis Res Ther 7:29–37

Basdeo SA et al (2015) Polyfunctional, pathogenic CD161+ Th17 lineage cells are resistant to regulatory T cell-mediated suppression in the context of autoimmunity. J Immunol 195:528–540

Choy EH et al (1996) Percentage of anti-CD4 monoclonal antibody-coated lymphocytes in the rheumatoid joint is associated with clinical improvement. Implications for the development of immunotherapeutic dosing regimens. Arthritis Rheum 39:52–56

Veale DJ et al (1999) Intra-articular primatised anti-CD4: efficacy in resistant rheumatoid knees. A study of combined arthroscopy, magnetic resonance imaging, and histology. Ann Rheum Dis 58:342–349

Mason U et al (2002) CD4 coating, but not CD4 depletion, is a predictor of efficacy with primatized monoclonal anti-CD4 treatment of active rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol 29:220–229

Rao DA et al (2017) Pathologically expanded peripheral T helper cell subset drives B cells in rheumatoid arthritis. Nature 542:110–114

Porter D et al (2016) Tumour necrosis factor inhibition versus rituximab for patients with rheumatoid arthritis who require biological treatment (ORBIT): an open-label, randomised controlled, non-inferiority, trial. Lancet 388:239–247

Teng YK et al (2007) Immunohistochemical analysis as a means to predict responsiveness to rituximab treatment. Arthritis Rheum 56:3909–3918

Humby F et al (2009) Ectopic lymphoid structures support ongoing production of class-switched autoantibodies in rheumatoid synovium. PLoS Med 6(1):e1. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.0060001

Amara K et al (2013) Monoclonal IgG antibodies generated from joint-derived B cells of RA patients have a strong bias toward citrullinated autoantigen recognition. J Exp Med 210:445–455

Bugatti S et al (2014) High expression levels of the B cell chemoattractant CXCL13 in rheumatoid synovium are a marker of severe disease. Rheumatology (Oxford) 53:1886–1895

Rombouts Y et al (2016) Extensive glycosylation of ACPA-IgG variable domains modulates binding to citrullinated antigens in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 75:578–585

Fassbender HG, Simmling-Annefeld M (1983) The potential aggressiveness of synovial tissue in rheumatoid arthritis. J Pathol 139:399–406

Mor A et al (2005) The fibroblast-like synovial cell in rheumatoid arthritis: a key player in inflammation and joint destruction. Clin Immunol 115:118–128

Korb A et al (2009) Cell death in rheumatoid arthritis. Apoptosis 14:447–454. doi:10.1007/s10495-009-0317-y

Seemayer CA et al (2003) Cartilage destruction mediated by synovial fibroblasts does not depend on proliferation in rheumatoid arthritis. Am J Pathol 162:1549–1557

Vallejo AN et al (2003) Synoviocyte-mediated expansion of inflammatory T cells in rheumatoid synovitis is dependent on CD47-thrombospondin 1 interaction. J Immunol 171:1732–1740

Abeles AM, Pillinger MH (2006) The role of the synovial fibroblast in rheumatoid arthritis: cartilage destruction and the regulation of matrix metalloproteinases. Bull NYU Hosp Jt Dis 64:20–24

Burmester GR et al (1997) Mononuclear phagocytes and rheumatoid synovitis. Mastermind or workhorse in arthritis? Arthritis Rheum 40:5–18

Tolboom TCA et al (2005) Invasiveness of fibroblast-like synoviocytes is an individual patient characteristic associated with the rate of joint destruction in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 52:1999–2002

Darnell JE et al (1994) Jak-STAT pathways and transcriptional activation in response to IFNs and other extracellular signaling proteins. Science 264:1415–1421

Leonard WJ, O'Shea JJ (1998) Jaks and STATs: biological implications. Annu Rev Immunol 16:293–322

Ghoreschi K et al (2011) Modulation of innate and adaptive immune responses by tofacitinib (CP-690,550). J Immunol 186:4234–4243

Burmester GR (2013) Tofacitinib (CP-690,550) in combination with methotrexate in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis with an inadequate response to tumour necrosis factor inhibitors: a randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet 381:451–460

van der Heijde D et al (2013) Tofacitinib (CP-690,550) in patients with rheumatoid arthritis receiving methotrexate: twelve-month data from a twenty-four-month phase III randomized radiographic study. Arthritis Rheum 65:559–570

Lee YH et al (2015) Comparative efficacy and safety of tofacitinib, with or without methotrexate, in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis: a Bayesian network meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Rheumatol Int 35:1965–1974

Boyle DL et al (2015) The JAK inhibitor tofacitinib suppresses synovial JAK1-STAT signalling in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 74:1311–1316

Distler JHW et al (2004) Physiologic responses to hypoxia and implications for hypoxia-inducible factors in the pathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 50:10–23

Harty LC et al (2012) Mitochondrial mutagenesis correlates with the local inflammatory environment in arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 71(4):582–588

Chang X, Wei C (2011) Glycolysis and rheumatoid arthritis. Int J Rheum Dis 14:217–222. doi:10.1111/j.1756-185X.2011.01598.x

Henderson B et al (1979) Glycolytic activity in human synovial lining cells in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 38:63–67

Biniecka M et al (2016) Dysregulated bioenergetics: a key regulator of joint inflammation. Ann Rheum Dis 75:2192–2200. doi:10.1136/annrheumdis-2015-208476

Frantz MC, Wipf P (2010) Mitochondria as a target in treatment. Environ Mol Mutagen 51:462–475

Zapico SC, Ubelaker DH (2013) mtDNA mutations and their role in aging, diseases and forensic sciences. Aging Dis 4:364–380

Poli G et al (2008) 4-hydroxynonenal: a membrane lipid oxidation product of medicinal interest. Med Res Rev 28:569–631

Taylor RW, Turnbull DM (2005) Mitochondrial DNA mutations in human disease. Nat Rev Genet 6:389–402

Ospelt C, Gay S (2005) Somatic mutations in mitochondria: the chicken or the egg? Arthritis Res Ther 7:179–180

Biniecka M et al (2011) Hypoxia induces mitochondrial mutagenesis and dysfunction in inflammatory arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 63:2172–2182

Biniecka M et al (2010) Oxidative damage in synovial tissue is associated with in vivo hypoxic status in the arthritic joint. Ann Rheum Dis 69:1172–1178

Tannahill GM et al (2013) Succinate is an inflammatory signal that induces IL-1β through HIF-1α. Nature 496:238–242

Biniecka M et al (2014) Redox-mediated angiogenesis in the hypoxic joint of inflammatory arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol 66:3300–3310

Szalay B et al (2014) The impact of conventional DMARD and biological therapies on CD4+ cell subsets in rheumatoid arthritis: a follow-up study. Clin Rheumatol 33:175–185

Masson-Bessiere C et al (2000) In the rheumatoid pannus, anti-filaggrin autoantibodies are produced by local plasma cells and constitute a higher proportion of IgG than in synovial fluid and serum. Clin Exp Immunol 119:544–552

Masson-Bessiere C et al (2001) The major synovial targets of the rheumatoid arthritis-specific antifilaggrin autoantibodies are deiminated forms of the alpha- and beta-chains of fibrin. J Immunol 166:4177–4184

Reparon-Schuijt CC et al (2001) Secretion of anti-citrulline-containing peptide antibody by B lymphocytes in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 44:41–47

Sebbag M et al (2006) Epitopes of human fibrin recognized by the rheumatoid arthritis-specific autoantibodies to citrullinated proteins. Eur J Immunol 36:2250–2263

Chang X et al (2005) Citrullination of fibronectin in rheumatoid arthritis synovial tissue. Rheumatology (Oxford) 44:1374–1382

Vossenaar ER, van Venrooij WJ (2004) Citrullinated proteins: sparks that may ignite the fire in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Res Ther 6:107–111

van Venrooij WJ et al (2008) Anti-CCP antibody, a marker for the early detection of rheumatoid arthritis. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1143:268–285

van Gaalen F et al (2005) The devil in the details: the emerging role of anticitrulline autoimmunity in rheumatoid arthritis. J Immunol 175:5575–5580

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

This article is a contribution to the special issue on Immunopathology of Rheumatoid Arthritis - Guest Editors: Cem Gabay and Paul Hasler

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Veale, D.J., Orr, C. & Fearon, U. Cellular and molecular perspectives in rheumatoid arthritis. Semin Immunopathol 39, 343–354 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00281-017-0633-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00281-017-0633-1