Abstract

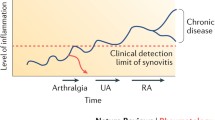

The detection of biomarkers in the preclinical phase of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and recent therapeutic advances suggest that it may be possible to identify and treat persons at high risk and to prevent the development of RA. Several trials are ongoing to test the efficacy of a therapeutic intervention in primary prevention. This paper reviews potential populations that might be considered for preventative medication. Further, we review the medications that are being explored to treat individuals considered at high risk of developing RA. Finally, in a group of asymptomatic individuals at high risk of developing RA, we assessed which factors mattered most when considering a preventive therapeutic intervention and what type of preventive treatment would be most acceptable to them. Understanding subjects’ perceptions of risks and benefits and willingness to undergo preventive therapy will be important in designing and implementing screening and preventive strategies.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

Majka DS, Holers VM. Can we accurately predict the development of rheumatoid arthritis in the preclinical phase? Arthritis Rheum. 2003;48(10):2701–5.

Bowman MA, Leiter EH, Atkinson MA. Prevention of diabetes in the NOD mouse: implications for therapeutic intervention in human disease. Immunol Today. 1994;15(3):115–20.

Van Dongen H, Van Aken J, Lard LR, Visser K, Ronday HK, Hulsmans HMJ, et al. Efficacy of methotrexate treatment in patients with probable rheumatoid arthritis. A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56(5):1424–32.

Nielen MM, van Schaardenburg D, Reesink HW, van de Stadt RJ, van der Horst-Bruinsma IE, de Koning MH, et al. Specific autoantibodies precede the symptoms of rheumatoid arthritis: a study of serial measurements in blood donors. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50(2):380–6.

Rantapaa-Dahlqvist S, de Jong BA, Berglin E, Hallmans G, Wadell G, Stenlund H, et al. Antibodies against cyclic citrullinated peptide and IgA rheumatoid factor predict the development of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;48(10):2741–9.

McClure A, Lunt M, Eyre S, Ke X, Thomson W, Hinks A, et al. Investigating the viability of genetic screening/testing for RA susceptibility using combinations of five confirmed risk loci. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2009;48(11):1369–74.

Organisation WH, editor. Preventing chronic disease: a vital investment. WHO Press; 2005.

Neuner JM, Schapira MM. Patient perceptions of osteoporosis treatment thresholds. J Rheumatol. 2014;41(3):516–22. doi:10.3899/jrheum.130548.

Harmsen CG, Stovring H, Jarbol DE, Nexoe J, Gyrd-Hansen D, Nielsen JB, et al. Medication effectiveness may not be the major reason for accepting cardiovascular preventive medication: a population-based survey. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2012;12:89. doi:10.1186/1472-6947-12-89.

Novotny F, Haeny S, Hudelson P, Escher M, Finckh A. Primary prevention of rheumatoid arthritis: a qualitative study in a high-risk population. Joint Bone Spine. 2013;80(6):673–4. doi:10.1016/j.jbspin.2013.05.005. A qualitative study exploring expectations and level of interest of high-risk individuals for RA regarding preventive interventions. Identified a minimum level of risk for developing RA above which participants are considering taking prophylactic treatment.

Laba TL, Brien JA, Fransen M, Jan S. Patient preferences for adherence to treatment for osteoarthritis: the MEdication Decisions in Osteoarthritis Study (MEDOS). BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2013;14:160. doi:10.1186/1471-2474-14-160.

Fraenkel L, Bogardus Jr ST, Concato J, Wittink DR. Treatment options in knee osteoarthritis: the patient’s perspective. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164(12):1299–304. doi:10.1001/archinte.164.12.1299.

Eisingerich AB, Wheelock A, Gomez GB, Garnett GP, Dybul MR, Piot PK. Attitudes and acceptance of oral and parenteral HIV preexposure prophylaxis among potential user groups: a multinational study. PLoS One. 2012;7(1):e28238. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0028238.

Maisonneuve AS, Huiart L, Rabayrol L, Horsman D, Didelot R, Sobol H, et al. Acceptability of cancer chemoprevention trials: impact of the design. Int J Med Sci. 2008;5(5):244–7.

Busso N, Karababa M, Nobile M, Rolaz A, Van Gool F, Galli M, et al. Pharmacological inhibition of nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase/visfatin enzymatic activity identifies a new inflammatory pathway linked to NAD. PLoS One. 2008;3(5):e2267. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0002267.

Silman AJ, Hennessy E, Ollier B. Incidence of rheumatoid arthritis in a genetically predisposed population. Br J Rheumatol. 1992;31(6):365–8.

Chibnik LB, Keenan BT, Cui J, Liao KP, Costenbader KH, Plenge RM, et al. Genetic risk score predicting risk of rheumatoid arthritis phenotypes and age of symptom onset. PLoS One. 2011;6(9):e24380. The study proposes a combination of various genetic risk factors combined into a single measure of genetic risk (genetic risk score).

Costenbader KH, Karlson EW. Epstein-Barr virus and rheumatoid arthritis: is there a link? Arthritis Res Ther. 2006;8(1):204.

Hart JE, Laden F, Puett RC, Costenbader KH, Karlson EW. Exposure to traffic pollution and increased risk of rheumatoid arthritis. Environ Health Perspect. 2009;117(7):1065–9.

Lu B, Solomon DH, Costenbader KH, Keenan BT, Chibnik LB, Karlson EW. Alcohol consumption and markers of inflammation in women with preclinical rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62(12):3554–9.

Kallberg H, Jacobsen S, Bengtsson C, Pedersen M, Padyukov L, Garred P, et al. Alcohol consumption is associated with decreased risk of rheumatoid arthritis: results from two Scandinavian case-control studies. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68(2):222–7.

Karlson EW, Mandl LA, Hankinson SE, Grodstein F. Do breast-feeding and other reproductive factors influence future risk of rheumatoid arthritis? Results from the Nurses’ Health Study. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50(11):3458–67.

Klareskog L, Stolt P, Lundberg K, Kallberg H, Bengtsson C, Grunewald J, et al. A new model for an etiology of rheumatoid arthritis: smoking may trigger HLA-DR (shared epitope)-restricted immune reactions to autoantigens modified by citrullination. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54(1):38–46.

Criswell LA, Saag KG, Mikuls TR, Cerhan JR, Merlino LA, Lum RF, et al. Smoking interacts with genetic risk factors in the development of rheumatoid arthritis among older Caucasian women. Ann Rheum Dis. 2006;65(9):1163–7.

Padyukov L, Silva C, Stolt P, Alfredsson L, Klareskog L. A gene-environment interaction between smoking and shared epitope genes in HLA-DR provides a high risk of seropositive rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2004.

Keenan BT, Chibnik LB, Cui J, Ding B, Padyukov L, Kallberg H, et al. Effect of interactions of glutathione S-transferase T1, M1, and P1 and HMOX1 gene promoter polymorphisms with heavy smoking on the risk of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62(11):3196–210.

Jorgensen KT, Wiik A, Pedersen M, Hedegaard CJ, Vestergaard BF, Gislefoss RE, et al. Cytokines, autoantibodies and viral antibodies in premorbid and postdiagnostic sera from patients with rheumatoid arthritis: case-control study nested in a cohort of Norwegian blood donors. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008;67(6):860–6. doi:10.1136/ard.2007.073825.

Karlson EW, Chibnik LB, Tworoger SS, Lee IM, Buring JE, Shadick NA, et al. Biomarkers of inflammation and development of rheumatoid arthritis in women from two prospective cohort studies. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;60(3):641–52. doi:10.1002/art.24350.

Nishimura K, Sugiyama D, Kogata Y, Tsuji G, Nakazawa T, Kawano S, et al. Meta-analysis: diagnostic accuracy of anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide antibody and rheumatoid factor for rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146(11):797–808.

Avouac J, Gossec L, Dougados M. Diagnostic and predictive value of anti-cyclic citrullinated protein antibodies in rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic literature review. Ann Rheum Dis. 2006;65(7):845–51.

Karlson EW, Ding B, Keenan BT, Liao K, Costenbader KH, Klareskog L, et al. Association of environmental and genetic factors and gene-environment interactions with risk of developing rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care Res. 2013;65(7):1147–56. doi:10.1002/acr.22005. Illustrates how both genetic tests and epidemiologic risk factors can be combined to identify individuals at high risk of developing RA.

Sparks JA, Chen CY, Jiang X, Askling J, Hiraki LT, Malspeis S, et al. Improved performance of epidemiologic and genetic risk models for rheumatoid arthritis serologic phenotypes using family history. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014. doi:10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-205009.

Scott IC, Seegobin SD, Steer S, Tan R, Forabosco P, Hinks A, et al. Predicting the risk of rheumatoid arthritis and its age of onset through modelling genetic risk variants with smoking. PLoS Genet. 2013;9(9):e1003808. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1003808.

Turk SA, van Beers-Tas MH, van Schaardenburg D. Prediction of future rheumatoid arthritis. Rheum Dis Clin N Am. 2014;40(4):753–70. doi:10.1016/j.rdc.2014.07.007.

van de Stadt LA, Witte BI, Bos WH, van Schaardenburg D. A prediction rule for the development of arthritis in seropositive arthralgia patients. Ann Rheum Dis. 2013;72(12):1920–6. doi:10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-202127. Proposes a functional prediction rule to identify individuals at high risk of developing RA.

Karlson EW, van Schaardenburg D, van der Helm-van Mil AH. Strategies to predict rheumatoid arthritis development in at-risk populations. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2016;55(1):6–15. doi:10.1093/rheumatology/keu287.

Klareskog L, Gregersen PK, Huizinga TW. Prevention of autoimmune rheumatic disease: state of the art and future perspectives. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69(12):2062–6. doi:10.1136/ard.2010.142109.

Bykerk VP, Hazes JM. When does rheumatoid arthritis start and can it be stopped before it does? Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69(3):473–5. doi:10.1136/ard.2009.116020.

Deane KD. Can rheumatoid arthritis be prevented? Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2013;27(4):467–85. doi:10.1016/j.berh.2013.09.002.

Finckh A, Deane KD. Prevention of rheumatic diseases: strategies, caveats, and future directions. Rheum Dis Clin N Am. 2014;40(4):771–85. doi:10.1016/j.rdc.2014.07.010.

de Jong HJ, Klungel OH, van Dijk L, Vandebriel RJ, Leufkens HG, van der Laan J, et al. Use of statins is associated with an increased risk of rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2012;71:648–54.

Tascilar K, Dell’Aniello S, Hudson M, Suissa S. Statins and the risk of rheumatoid arthritis—a population based study from the General Practice Research Database. Quebec City: Canadian Rheumatology Association Annual Meeting; 2015.

Gan RW, Young KA, Zerbe GO, Demoruelle MK, Weisman MH, Buckner JH, et al. Lower omega-3 fatty acids are associated with the presence of anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide autoantibodies in a population at risk for future rheumatoid arthritis: a nested case-control study. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2016;55(2):367–76. doi:10.1093/rheumatology/kev266.

Bos WH, Dijkmans BA, Boers M, van de Stadt RJ, van Schaardenburg D. Effect of dexamethasone on autoantibody levels and arthritis development in patients with arthralgia: a randomised trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69(3):571–4. doi:10.1136/ard.2008.105767.

Tak P. Prevention of clinically manifest rheumatoid arthritis by B cell directed therapy in the earliest phase of the disease. In: Nederland Trial Register. Dutch Cochrane Centre, Academisch Medisch Centrum, Amsterdam. 2012. http://www.trialregister.nl/trialreg/admin/rctview.asp?TC=2442. Accessed 18 July 2012.

Tak PP. Towards prevention of RA by B cell directed therapy: the PRAIRI study. 36th Eueopean Workshop for Rheumatology Research; 2016 27 Feb 2016; York.

Neff T. Rheumatoid arthritis prevention study getting ready to roll. UCHealth Insider 2015.

Al-Laith M, Cope AP. Arthritis prevention in the pre-clinical phase of rheumatoid arthritis with abatacept (APIPPRA). ISRCTN registry 2014.

van den Bemt BJ, Zwikker HE, van den Ende CH. Medication adherence in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a critical appraisal of the existing literature. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2012;8(4):337–51. doi:10.1586/eci.12.23.

Finckh A, Müller R, Möller B, Dudler J, Kyburz D, Walker U et al. A novel screening strategy for preclinical rheumatoid arthritis (RA) in first degree relatives of patients with RA. Annual European Congress of Rheumatology EULAR; 2011; London: Ann Rheum Dis.

Aslibekyan S, Sha J, Redden DT, Moreland LW, O’Dell JR, Curtis JR, et al. Gene-body mass index interactions are associated with methotrexate toxicity in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73(4):785–6. doi:10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204263.

Kaufmann J, Kielstein V, Kilian S, Stein G, Hein G. Relation between body mass index and radiological progression in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2003;30(11):2350–5.

Kanninen BJ. Optimal design for multinomial choice experiments. J Mark Res. 2002;39(2):214–27.

Nichols, Austin, Schaffer M. Clustered errors in Stata. ited Kingdom Stata Users’ Group Meeting; 2007.

Tak P. Prevention of clinically manifest rheumatoid arthritis by B cell directed therapy in the earliest phase of the disease. PRAIRI. In: International Clinical Trials Platform. WHO, Geneva. 2010. Accessed 13 March 2012.

Fautrel B, Clarke AE, Guillemin F, Adam V, St-Pierre Y, Panaritis T, et al. Valuing a hypothetical cure for rheumatoid arthritis using the contingent valuation methodology: the patient perspective. J Rheumatol. 2005;32(3):443–53.

Taylor HA, Sugarman J, Pisetsky DS, Bathon J. Formative research in clinical trial development: attitudes of patients with arthritis in enhancing prevention trials. Ann Rheum Dis. 2007;66(4):542–4.

Ropka ME, Keim J, Philbrick JT. Patient decisions about breast cancer chemoprevention: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(18):3090–5. doi:10.1200/JCO.2009.27.8077.

Waters EA, Weinstein ND, Colditz GA, Emmons K. Explanations for side effect aversion in preventive medical treatment decisions. Health Psychol. 2009;28(2):201–9. doi:10.1037/a0013608.

Marshall IJ, Wolfe CD, McKevitt C. Lay perspectives on hypertension and drug adherence: systematic review of qualitative research. BMJ. 2012;345:e3953. doi:10.1136/bmj.e3953.

Scoville EA, Ponce de Leon Lovaton P, Shah ND, Pencille LJ, Montori VM. Why do women reject bisphosphonates for osteoporosis? A videographic study. PLoS One. 2011;6(4):e18468. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0018468.

Fried TR, Tinetti ME, Towle V, O’Leary JR, Iannone L. Effects of benefits and harms on older persons’ willingness to take medication for primary cardiovascular prevention. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(10):923–8. doi:10.1001/archinternmed.2011.32.

Llewellyn-Thomas HA, Paterson JM, Carter JA, Basinsk A, Myers MG, Hardacre GD, et al. Primary prevention drug therapy: can it meet patients’ requirements for reduced risk? Med Decis Mak. 2002;22(4):326–39.

Fraenkel L, Gulanski B, Wittink D. Patient willingness to take teriparatide. Patient Educ Couns. 2007;65(2):237–44. doi:10.1016/j.pec.2006.08.004.

Smerecnik CM, Mesters I, Verweij E, de Vries NK, de Vries H. A systematic review of the impact of genetic counseling on risk perception accuracy. J Genet Couns. 2009;18(3):217–28. doi:10.1007/s10897-008-9210-z.

Carling CL, Kristoffersen DT, Montori VM, Herrin J, Schunemann HJ, Treweek S, et al. The effect of alternative summary statistics for communicating risk reduction on decisions about taking statins: a randomized trial. PLoS Med. 2009;6(8):e1000134. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1000134.

Peters E, Hart PS, Fraenkel L. Informing patients: the influence of numeracy, framing, and format of side effect information on risk perceptions. Med Decis Mak. 2011;31(3):432–6. doi:10.1177/0272989X10391672.

Elwyn G, O’Connor A, Bennett C, Newcombe R, Politi M, Durand M, et al. Assessing the quality of decision support technologies using the International Patient Decision Aid Standards instrument (IPDASi). PLoS One. 2010;4(3):e4705.

Acknowledgments

We thank Mehdi Najafzadeh for his assistance with the analysis of the data.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

AF, ME, MHL, and NB declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

All reported experiments with human subjects performed by the authors were in compliance with all applicable ethical standards (including the Helsinki Declaration and its amendments, institutional research committee standards, and national guidelines).

Funding

This work was supported by the Swiss National Science Foundation [3200B0_120639/1].

Additional information

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Health Economics and Quality of Life

Appendices

Appendix: Background information and instructions to this binary choice questionnaire

Explanation about the study

In the following sections, we will present various preventive treatment options. Each treatment option is associated with 4 characteristics. These attributes are the following:

-

Reduction in the risk of developing rheumatoid arthritis (RA)

-

Risk of having a major side effect related to the preventive treatment

-

Risk of having a minor side effect related to the preventive treatment

-

How the treatment is administered

For each treatment option, we ask you to choose the attribute that you find best and the feature you find worst.

Following this step, we will present you a hypothetical risk of developing RA and ask you whether, with such a risk, you would take the treatment option presented previously or not. Note that the proposed treatment would cost you nothing.

Attributes of the treatment options

Each treatment option has a unique combination of attributes. We will briefly detail these attributes.

-

1.

Reduction in the risk of developing rheumatoid arthritis:

This refers to the effectiveness of treatment. By taking a drug, we hope to reduce the risk of developing rheumatoid arthritis (RA). However, currently, we do not yet know precisely the effectiveness of the preventive treatment. The treatment could only delay the onset of the disease or it could completely prevent its occurrence. This is called risk reduction in developing the disease.

Example:

Suppose your initial risk of developing the disease was 50 % (or 1 chance in 2). If a preventive treatment decreased the risk of developing RA by 75 % (or a 75 % risk reduction in developing RA), then your risk of developing the disease would be reduced to 12.5 % (or 1 chance in 8 ).

The options offered in the questionnaire are

-

0 % (taking therapy will only delay the onset of RA).

-

20 % (or 1 in 5 will not develop RA because of the treatment).

-

40 % (or 2 out of 5 people will not develop RA because of treatment).

-

80 % (or 4 out of 5 people will not develop RA because of treatment).

-

-

2.

Risk of a major side effect

Here, we refer to an adverse event due to the treatment that would result in hospitalization or require specific treatment. For example, a major side effect could be an infection with an unusual microorganism, requiring treatment with antibiotics. These types of infection usually heal without permanent damage. However, there remains the possibility such an infection may be life-threatening.

In order to be consistent with the wording of the other questions, we present the risk of major side effects as “the chance not to develop a major side effect.” The options offered in the questionnaire are

-

>99 % chances not to develop a major side effect (= less than one in 100 persons will experience a major side effect).

-

95 % chances not to develop a major side effect (=5 out 100 persons will experience a major side effect).

-

90 % chances not to develop a major side effect (= 10 out 100 persons will experience a major side effect).

-

80 % chances not to develop a major side effect (= 20 out 100 persons will experience a major side effect).

-

-

3.

Probability of a minor side effect

Minor side effects normally require no treatment. Examples of these side effects may include headaches, transient flu-like symptoms, or a localized skin reaction.

In order to be consistent with the wording of the other questions, we present the risk of major side effects as “the chance not to develop a minor side effect”. The options offered in the questionnaire are

-

95 % chances not to develop a minor side effect (= 5 out 100 persons will experience a minor side effect).

-

90 % chances not to develop a minor side effect (= 10 out 100 persons will suffer a major side effect).

-

80 % chances not to develop a minor side effect (= 20 out 100 persons will suffer a major side effect).

-

60 % chances not to develop a minor side effect (= 40 out 100 persons will suffer a major side effect).

-

-

4.

How the treatment is administered

The proposed medications are antirheumatic treatments commonly used for patients with RA (these are not experimental drugs). As preventive treatments, we believe they should be taken for at least a year.

There are different ways these drugs may be administered:

-

Tablets to be taken daily by mouth (oral).

-

A subcutaneous injection (under the skin prick), self-administered every two weeks.

-

A monthly intravenous infusion (short-term infusion in the hospital: ½ - 1 hour).

-

1 or 2 single intravenous infusion (longer infusion in the hospital: 4-5 hours).

-

Reduction in the risk of developing RA

We first present you a hypothetical risk of developing RA. These different levels of risk are evaluated based on test results, similar to those you have just performed.

The level of risk that you are presented are

-

1 % (=1 in 100 people will develop the disease)

-

20 % (=1 in 5 will develop the disease)

-

40 % (=2 out of 5 people will develop the disease)

-

80 % (=4 out of 5 people will develop the disease)

Given such a risk, we will then ask you whether you would take the treatment option presented previously or not.

_______

On the following pages, nine different treatment options will be presented. You will then be asked to choose the best and worst feature for each option, and you may decide whether or not take the proposed treatment.

We are aware that issues may seem repetitive, but we are very interested to see how you respond to each of them.

Please press “Next” to see an example question.

Figure 1 Sample task of the of binary choice questionnaire

Question 1

Below is an example of a potential treatment that you could be offered to reduce your risk of developing rheumatoid arthritis. Please pick the feature that you consider the best among the characteristics of this preventive treatment. Also please choose the worst feature of the proposed preventive treatment.

We remind you that the proposed treatment would cost you nothing (fully supported) and that the therapy duration is at least one year (with the exception of the intravenous infusion therapy which has a very long duration).

Which of the attributes below would you consider the best and the worst attribute of the proposed preventive treatment?

Treatment | Best | Worst |

|---|---|---|

20 % risk reduction in risk of developing RA: | ✓ | |

80 % risk of not developing a mild side effect | ||

95 % risk of not developing a mild side effect | ||

Oral daily tablet for one year | ✓ |

Now, assuming that the analyses of your blood tests predict a risk of 1 % (1 in 100 chance) of developing rheumatoid arthritis, would you take the treatment described above?

YES / NO

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Finckh, A., Escher, M., Liang, M.H. et al. Preventive Treatments for Rheumatoid Arthritis: Issues Regarding Patient Preferences. Curr Rheumatol Rep 18, 51 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11926-016-0598-4

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11926-016-0598-4