Abstract

Juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA) is an autoimmune disease of childhood requiring treatment with immune modulation therapy. It runs a relapsing and remitting course, with approximately half of affected children continuing with active disease into adult life. Defining clinical remission is challenging, but necessary, as it is critical in determining when potentially toxic therapy can be stopped. We found that preliminary consensus criteria for defining JIA remission are not being used in full by a representative sample of UK pediatric rheumatologists. Extending the period of remission, whilst on synthetic diseasemodifying anti-rheumatic drug (DMARD) medication, beyond 6 months does not seem to reduce the risk of relapse once medication is stopped. However, we found that most clinicians state that they still require at least 1 year in remission before DMARD withdrawal. There is increasing evidence that subclinical biomarkers may help to assess disease activity, and therefore aid clinicians in determining remission. In this review we argue that agreement on remission criteria and optimum timing of DMARD withdrawal is crucial for consistent clinical practice, and further research in this area is needed.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Manners PJ, Bower C. Worldwide prevalence of juvenile arthritis why does it vary so much? J Rheumatol 2002; 29(7): 1520–30

Petty RE, Southwood TR, Manners P, et al. International League of Associations for Rheumatology classification of juvenile idiopathic arthritis: second revision, Edmonton, 2001. J Rheumatol 2004; 31: 390–2

Oen K, Malleson PN, Cabral DA, et al. Disease course and outcome of juvenile rheumatoid arthritis in a multicenter cohort. J Rheumatol 2002; 29: 1989–99

Lovell DJ, Ruperto N, Goodman S, et al. Adalimumab with or without methotrexate in juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med 2008; 359(8): 810–20

Giannini EH, Brewer EJ, Kuzmina N, et al. Methotrexate in resistant juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. Results of the U.S.A.-U.S.S.R. double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. The Pediatric Rheumatology Collaborative Study Group and The Cooperative Children’s Study Group. N Engl J Med 1992; 326(16): 1043–9

Packham JC, Hall MA. Long-term follow-up of 246 adults with juvenile idiopathic arthritis: functional outcome. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2002; 41(12): 1428–35

Wallace CA, Ruperto N, Giannini E, et al. Preliminary criteria for clinical remission for select categories of juvenile idiopathic arthritis. J Rheumatol 2004; 31(11): 2290–4

Wallace CA, Huang B, Bandeira M, et al. Patterns of clinical remission in select categories of juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 2005; 52(11): 3554–62

Wallace CA, Ravelli A, Huang B, et al. Preliminary validation of clinical remission criteria using the OMERACT filter for select categories of juvenile idiopathic arthritis. J Rheumatol 2006; 33(4): 789–95

Flatø B, Lien G, Smerdel A, et al. Prognostic factors in juvenile rheumatoid arthritis: a case-control study revealing early predictors and outcome after 14.9 years. J Rheumatol 2003; 30(2): 386–93

Marti P, Molinari L, Bolt IB, et al. Factors influencing the efficacy of intra-articular steroid injections in patients with juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Eur J Pediatr 2008; 167(4): 425–30

Albers HM, Brinkman DM, Kamphuis SS, et al. Clinical course and prognostic value of disease activity in the first two years in different subtypes of juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2010; 62(2): 204–12

Vilca I, Munitis PG, Pistorio A, et al. Predictors of poor response to methotrexate in polyarticular-course juvenile idiopathic arthritis: analysis of the PRINTO methotrexate trial. Ann Rheum Dis 2010; 69(8): 1479–83

Hull RG. Management guidelines for arthritis in children. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2001; 40(11): 1308

Davies K, Cleary G, Foster H, et al. BSPAR standards of care for children and young people with juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2010; 49(7): 1406–8

Woo P. Theoretical and practical basis for early aggressive therapy in paediatric autoimmune disorders. Curr Opin Rheumatol 2009; 21(5): 552–7

Prince FH, Otten MH, van Suijlekom-Smit LW. Diagnosis and management of juvenile idiopathic arthritis. BMJ 2010; 341: c6434

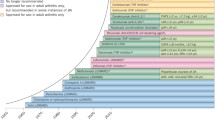

Beukelman T, Patkar NM, Saag KG, et al. American College of Rheumatology recommendations for the treatment of juvenile idiopathic arthritis: initiation and safety monitoring of therapeutic agents for the treatment of arthritis and systemic features. Arthritis Care Res 2011; 63: 465–82

Ruperto N, Murray KJ, Gerloni V, et al. A randomized trial of parenteral methotrexate comparing an intermediate dose with a higher dose in children with juvenile idiopathic arthritis who failed to respond to standard doses of methotrexate. Arthritis Rheum 2004; 50(7): 2191–201

Woo P, Southwood TR, Prieur AM, et al. Randomized, placebo-controlled, ircrossover trial of low-dose oral methotrexate in children with extended oli-goarticular or systemic arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 2000; 43(8): 1849–57

Ravelli A, Martini A. Juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Lancet 2007; 369(9563): 767–78

Mangge H, Kenzian H, Gallistl S, et al. Serum cytokines in juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. Correlation with conventional inflammation parameters and clinical subtypes. Arthritis Rheum 1995; 38(2): 211–20

Levinson JE, Wallace CA. Dismantling the pyramid. J Rheumatol Suppl 1992; 33: 6–10

Lovell D. Update on treatment of arthritis in children: new treatments, new goals. Bull NYU Hosp Jt Dis 2006; 64(1–2): 72–6

NICE. Guidance on the use of etanercept for the treatment of juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Technology appraisal no. 35. London: NICE, 2002

Lovell DJ, Reiff A, Ilowite NT, et al. Safety and efficacy of up to eight years of continuous etanercept therapy in patients with juvenile rheumatoid arthritis Arthritis Rheum 2008; 58(5): 1496–504

Southwood TR, Foster HE, Davidson JE, et al. Duration of etanercept treatment and reasons for discontinuation in a cohort of juvenile idiopathic arthritis patients. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2011; 50(1): 189–95

FDA. Tumor necrosis factor (TNF) blockers (marketed as Remicade, Enbrel, Humira, Cimzia, and Simponi) August 2009 [online]. Available from URL: http://www.fda.gov/Safety/MedWatch/SafetyInformation/SafetyAlertsforHumanMedicalProducts/ucm175843.htm [Accessed 2011 Oct]

Deighton C, Scott DL. Treating inflammatory arthritis early. BMJ 2010; 341:c7384

Foell D, Frosch M, Schulze zur Wiesch A, et al. Methotrexate treatment in juvenile idiopathic arthritis: when is the right time to stop? Ann Rheum Dis 2004; 63(2): 206–8

Foell D, Wulffraat N, Wedderburn LR, et al. Methotrexate withdrawal at 6 vs 12 months in juvenile idiopathic arthritis in remission: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2010; 303(13): 1266–73

Oen K, Malleson PN, Cabral DA, et al. Cytokine genotypes correlate with pain and radiologically defined joint damage in patients with juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2005; 44(9): 1115–21

Broughton T, Armon K. Juvenile idiopathic arthritis: how do clinicians define remission and withdraw etanercept? Arch Dis Child 2010; 95Suppl. 1: A23–38

Papsdorf V, Horneff G. Complete control of disease activity and remission induced by treatment with etanercept in juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2011; 50(1): 214–21

Lurati A, Salmaso A, Gerloni V, et al. Accuracy of Wallace criteria for clinical remission in juvenile idiopathic arthritis: a cohort study of 761 consecutive cases. J Rheumatol 2009; 36(7): 1532–5

Schulze zur Wiesch A, Foell D, Frosch M, et al. Myeloid related proteins MRP8/MRP14 may predict disease flares in juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2004; 22(3): 368–73

Frosch M, Ahlmann M, Vogl T, et al. The myeloid-related proteins 8 and 14 complex, a novel ligand of toll-like receptor 4, and interleukin-1beta form a positive feedback mechanism in systemic-onset juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 2009; 60(3): 883–91

Frosch M, Strey A, Vogl T, et al. Myeloid-related proteins 8 and 14 are specifically secreted during interaction of phagocytes and activated endothelium and are useful markers for monitoring disease activity in pauciarticular-onset juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 2000; 43: 628–37

Acknowledgments

No sources of funding were used to prepare this manuscript.

The Paediatric Rheumatology Department at the Norfolk and Norwich University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust has received funding from Wyeth Pharmaceuticals (the manufacturers of etanercept) to part fund a Pediatric Rheumatology Nurse Specialist for 3 years. Wyeth have also part funded an adolescent independence break for young people in the Eastern region, organized by Dr Armon and her team in 2009. Mr Broughton has no conflicts of interest to declare.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Broughton, T., Armon, K. Defining Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis Remission and Optimum Time for Disease-Modifying Anti-Rheumatic Drug Withdrawal. Pediatr Drugs 14, 7–12 (2012). https://doi.org/10.2165/11595980-000000000-00000

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.2165/11595980-000000000-00000